ARCHIVE - Summative Evaluation of the Phase II Expansion of the National Crime Prevention Strategy — Final Report

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Adobe Acrobat version (PDF 743KB)

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 1.1 The National Crime Prevention Strategy

- 1.2 Priority Groups of the NCPS

- 1.3 Phase I of the National Crime Prevention Strategy

- 1.4 Phase II of the National Crime Prevention Strategy

- 1.5 Phase II Expansion of the National Crime Prevention Strategy

- 1.6 NCPS Programs

- 1.7 Purpose and Organization of the Report

- 2. Evaluation Objectives and Issues

- 3. Methodology

- 4. Findings

- 4.1 Broader Participation in Crime Prevention

- 4.2 Increased Awareness/ Understanding of Crime Prevention

- 4.3 Identification/Adoption of Successful Crime Prevention Approaches

- 4.4 Increased Community Capacity to Respond to Crime

- 4.5 Enhanced Policy Planning and Development in Crime Prevention

- 4.6 Strengths and Weaknesses

- 4.7 Lessons Learned

- 4.8 Progress Since Mid-Term Evaluation

- 5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- 5.1 Overview

- 5.2 Document and File Review

- Appendix A: Matrix of Evaluation Issues, Indicators and Data Sources

- Appendix B: List of Documents Reviewed

- Appendix C: Administrative Data Tables

- Appendix D: List of Interviewees

- Appendix E: Regional Initiatives: Summary of Regional Directors’ Responses

List of Tables

Table 4.1 Percentage of Projects in Each Program by Contributor (Partner) Type

Table 4.2 Percentage of Projects in Each Program by Priority Group

Table 4.3 Contribution to NCPS Phase II Expansion Objectives

Executive Summary

Background

The findings of the Summative Evaluation of the Phase II Expansion of the National Crime Prevention Strategy (NCPS) are presented in this report. The NCPS is a federal initiative of the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC), designed to prevent crime and victimization in communities. Phase I of the Strategy was implemented in 1994, Phase II in 1998, and the expansion of Phase II in 2001. A mid-term evaluation of Phase II was conducted in the summer of 2000 and a number of recommendations were made to improve the effectiveness and delivery of the NCPS. A summative evaluation of Phase II was completed in December 2002. Later, a mid-term evaluation of the expansion of Phase II was completed in December of 2003.

Overview of Strategy

The National Crime Prevention Strategy is based on the principle that the surest way to reduce crime is to focus on the factors that put individuals at risk. The Strategy aims to reduce crime and victimization by addressing crime before it happens. Specifically, the objectives of the NCPS are:

- to promote integrated action of key governmental and non-governmental partners to reduce crime and victimization;

- to assist communities in developing and implementing community-based solutions to crime and victimization, particularly as they affect children, youth, women and Aboriginal persons; and

- to increase public awareness of and support for effective approaches to crime prevention.

The NCPS is based on the principle of crime prevention though social development (CPSD). CPSD is based on the philosophy that there is a need to balance law enforcement and corrections approaches to crime prevention, and to promote the reduction of victimization with social development approaches that recognize and address root causes of crime and victimization. CPSD involves identifying and addressing risk factors that are associated with criminal activity.

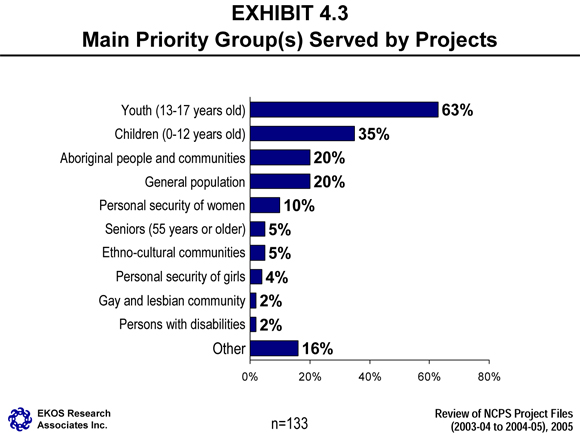

The NCPS is focused on four priority groups considered to be at particular risk with respect to crime and victimization: children; youth; Aboriginal peoples and communities; and the personal security of women and girls. In addition, the Strategy has broadened its reach to address other at-risk groups, including seniors, ethno-cultural groups, the gay and lesbian community, and persons with disabilities.

The Government of Canada launched Phase I of the National Strategy on Community Safety and Crime Prevention in 1994 (which was renamed the National Crime Prevention Strategy in 2002). Then, in 1998, Phase II of the National Strategy was implemented with an initial investment of $32 million annually.

Phase II Expansion of NCPS

In May 2001, the federal government announced the expansion of Phase II. At that time, the NCPS was comprised of three components – the National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC), the Safer Communities Initiative, and Promotion and Public Education. Two major changes occurred as a result of the expansion: the implementation of a fifth Safer Communities funding program, the Crime Prevention Strategic Fund (SF or Strategic Fund); and the implementation of an additional component to the Strategy, the Crime Prevention and Public Safety Initiative (CPPSI), which was not part of the present evaluation (because the CPPSI evaluation was the responsibility of the former Solicitor General of Canada).

The expansion of Phase II also included an additional investment of $145 million over four years (2001-2005). This additional funding was to provide more support for community projects, a strengthened infrastructure, and greater reach into every part of the country. The rationale underlying such a strategic investment was to reduce the burden of the traditional criminal justice system on taxpayers by stopping crimes before they occur. More specifically, the expansion was to allow the NCPS to do the following:

- undertake the development work required to make a difference in high-need, low-capacity communities, including inner-city, rural, remote, and Aboriginal communities;

- offer a continuum of supports and crime prevention models for communities that require a range of programming interventions;

- facilitate citizen engagement through broad and enduring public education efforts and informed discussion, again with an emphasis on high-risk, high-needs/low-capacity communities, and with a focus on sharing the best practices and success stories that can spur like-minded initiatives;

- expand the scope of relationships with non-traditional partners and deepen the range of efforts to priority areas, such as seniors and persons with disabilities; and

- establish a centre of excellence, expertise, and learn to work on crime prevention projects, research, policy, and practice.1

Over the course of the Phase II expansion, a variety of departmental and organizational changes have occurred. For instance, the NCPS and NCPC were originally under the direction of the Department of Justice, and later changed to the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC) during a reorganization of certain federal government departments. Furthermore, prior to the transfer of the Strategy from Justice to PSEPC, there was a hiring freeze the last two years while the Strategy was under the Department of Justice. In addition, NCPC has seen two Executive Directors come and go over the course of the expansion, and a third Executive Director came into the position in April 2005.

NCPS Components and Programs

The overall program design of the NCPS is reflected in the four key components including the National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC), the Safer Communities Initiative, the Promotion and Public Education Program (PPEP), and the Crime Prevention and Public Safety Initiative (CPPSI).

National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC): The NCPC is responsible for overall management and implementation of the NCPS and is the principal administrator of the NCPS. The NCPC activities include policy and strategic planning, coordination of activities within the federal government and between the federal and provincial/territorial governments, research and evaluation, and administration of funding programs (under the Safer Communities Initiative). Overall responsibility for the Centre rests with the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada. The NCPC serves as the federal government’s crime prevention policy centre. Though housed within the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, the NCPC is a separate organizational unit with its own funds administration.

Safer Communities Initiative: The second component of the NCPS, the Safer Communities Initiative, is administered by the NCPC and consists of grants and contributions funding programs. The Safer Communities Initiative is designed to assist Canadians in undertaking crime prevention activities in their communities through the development and implementation of programs — the Community Mobilization Program (CMP), the Crime Prevention Partnership Program (CPPP), the Business Action Program on Crime Prevention (BAP), the Crime Prevention Investment Fund (CPIF), and the Crime Prevention Strategic Fund (SF). These programs fund communities and organizations to develop, implement and evaluate CPSD models. All of these programs are overseen by a Director, Program Development and Delivery, who reports directly to the NCPC Executive Director.

Promotion and Public Education Program (PPEP): The Promotion and Public Education Program is intended to increase public awareness about the National Crime Prevention Strategy. The Communications, Promotion, and Public Education Team coordinates the PPEP and is responsible for media relations, public events and announcements, the production and distribution of NCPS publications and multimedia tools, the NCPS website, and the resource centre.

Crime Prevention and Public Safety Initiative (CPPSI): The CPPSI is in place to strengthen and build capacity in the areas of policing and corrections to address the root causes of crime. The focus is on crime and victimization issues in Aboriginal and remote/isolated communities, substance abuse awareness and prevention, addressing the risks associated with children and families of offenders, and developing strategies to deal with youth at risk. As noted, this component of the Strategy was not part of the present evaluation, because the evaluation of CPPSI was the responsibility of the former Solicitor General of Canada.

Evaluation Objectives and Issues

The overall objective of this evaluation was to support PSEPC’s inherited commitment to accountability for and evaluation of the expansion of Phase II of the NCPS. The evaluation focused on the achievements of the former Department of Justice component of the expansion of Phase II. The scope of the evaluation included the four years of the Phase II expansion (2001-02 to 2004-05) and all NCPS programs, with the exception of the CPPSI, which was evaluated separately.

The summative evaluation of the expansion of Phase II focused on assessing the degree to which the expansion has made progress toward and achieved its objectives/intended outcomes, given that the mid-term evaluation concentrated on design and delivery issues. The focus was on impacts, in particular, on what has been accomplished since the mid-term evaluation. Specific evaluation issues were related to: broader participation in crime prevention; increased awareness/understanding of crime prevention; identification and adoption of successful crime prevention approaches; increased community capacity to respond to crime; and enhanced policy planning and development in crime prevention. In addition, the evaluation assessed the strengths and weaknesses, challenges faced and lessons learned by the NCPS, and provided recommendations related to the renewal of the Strategy.

It should be noted as context that the NCPC has faced a variety of operational challenges, which have caused delays and hampered the implementation of the Phase II expansion of the NCPS. These challenges have included: overworked staff for the past two years due to budgetary constraints on staffing; the lack of a Director, Research and Evaluation for the past two years (the position has been vacant); and an overall climate of uncertainty as to the future of the NCPS, including the uncertainty associated with the end of the expansion sunset funding, which has led to high staff turnover. Moreover, the NCPS and the NCPC have shifted from the Department of Justice to the new Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC). The transition and adjustment to a new organizational environment and departmental culture clearly takes time. In assessing the progress and impacts of the Phase II expansion, these factors needed to be taken into account.

Methodology

The evaluation issues/questions were examined through the collection and analysis of information from the following sources/methods:

- Review of program and related documentation (e.g., previous evaluations/audits, research reports, communications materials such as media announcements and news releases, and documentation related to key funded projects in each region);

- Review of a random sample of completed projects (n=133) from 2003-04 and 2004-05 for which Final Reports had been submitted (as of February 1, 2005);

- Review of administrative data (from the NCPC’s Project Control System) on all funded projects over the four years of the Phase II expansion to provide a descriptive analysis of the Strategy; and

- Key informant interviews (n=20) with NCPC managers at the Ottawa office, NCPC Regional Directors, key Strategy partners, and external experts in community safety and crime prevention.

A matrix linking the evaluation issues with indicators and data sources/methods is provided in Appendix A. The data collection instruments are provided in a separate document.

Findings and Conclusions

Broader Participation in Crime Prevention

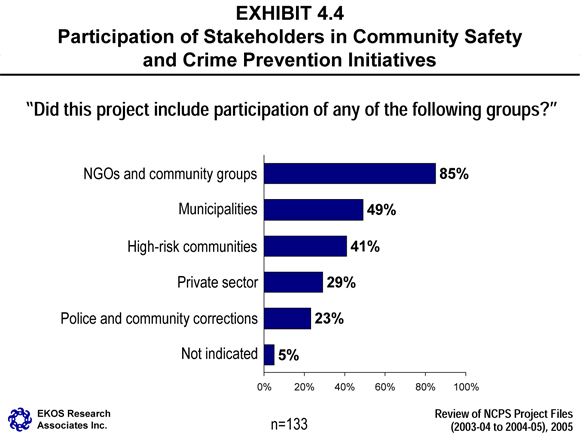

Evaluation findings from the key informant interviews and review of documentation, administrative data and files indicate that the expansion of the NCPS Phase II (and the associated additional funding) has helped to broaden the participation of various stakeholders in community safety and crime prevention initiatives, though participation is much greater from some groups than others. In particular, non-governmental organizations and community groups, the police and high-risk communities have participated significantly (i.e., as project sponsors, partners or participants) whereas there have been lower levels of participation by community correctional agencies and the private sector. The comparatively low level of participation from community corrections is not necessarily a negative finding, given that this stakeholder group is a primary focus of the CPPSI component of the Strategy, which was examined in a separate evaluation. Possible reasons for the lack of private sector involvement include NCPC staff/resource constraints, which make it difficult to expend the effort to engage the private sector; a lack of interest on the part of the some private sector organizations unless the crime prevention effort is clearly linked to business concerns; and the lack of clear procedures/mechanisms for the Strategy to attract private sector participation.

Regarding the degree of participation of municipalities (beyond municipal police agencies), the evaluation findings are mixed suggesting that municipal involvement has not been uniformly strong in all areas of the country. Nevertheless, there are numerous examples of relevant participation by some municipalities and through Comprehensive Community Initiatives as well as the involvement of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities.

The Strategy’s efforts over the Phase II expansion period (2001-02 to 2004-05), including the broadened participation of stakeholders, have made some contribution toward the objectives of the NCPS expansion. In particular, the evaluation findings suggest that there has been progress in facilitating citizenship engagement and public education, offering a continuum of supports/models for communities, and undertaking development work needed in high-need, low-capacity communities, though more work needs to be done on all fronts. In addition, key informants believe that a contribution has been made in expanding the scope of relationships with non-traditional partners and deepening efforts in priority areas (e.g., seniors, persons with disabilities, the gay and lesbian community, and ethno-cultural communities); however, the review of files and administrative data suggests that the contribution in reaching new priority groups has been modest to date. With respect to the fifth formal objective – establishing NCPC as a centre of excellence/expertise – the consensus is that this has not yet been achieved, even though a foundation has been laid with the crime prevention expertise of NCPC staff across the country.

Based on the mostly qualitative evidence gathered in this evaluation, it is reasonable to conclude that progress has been made toward the Phase II expansion objectives, as discussed above, but it is not possible to draw precise conclusions about the incremental contribution of the Strategy’s efforts and stakeholders’ involvement to these formal objectives.

Increased Awareness/Understanding of Crime Prevention

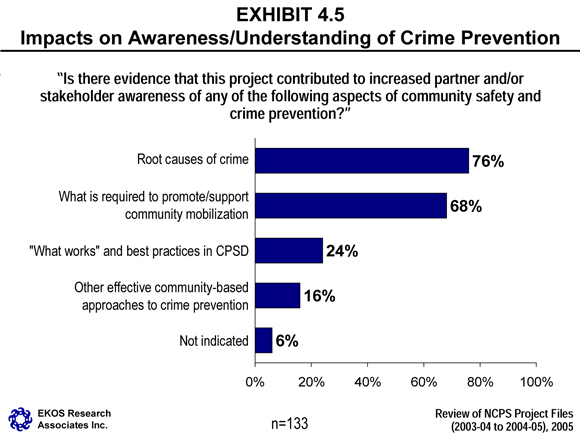

The evaluation findings indicate that the work of the Phase II expansion (e.g., delivery of workshops, distribution of information kits, conferences, public forums, research studies, NCPC networking efforts, making information available on the NCPC website and virtual library) has contributed to increasing awareness/understanding of community safety and crime prevention among partners and stakeholders. This includes an increase in understanding of the root causes of crime (demonstrated, for example, by the increasing quality of proposals for project funding) and of what is required to promote and support community mobilization in response to crime, though there may be a need for more specific guidelines on this matter. In addition, there is some evidence of increased awareness of best practices in CPSD and of other community-based approaches to crime prevention (e.g., the use of culturally appropriate approaches).

Findings from the file review and key informant interviews also suggest that public awareness and acceptance of crime prevention, including CPSD approaches, have been increased particularly in communities reached by Strategy projects. In addition, public opinion research commissioned by the Department of Justice (polls from July 2000 and November 2003) indicates that the Canadian public is generally aware and supportive of crime prevention through social development initiatives. For instance, Canadians correctly identify a number of CPSD root causes as having an impact on crime and rate a number of CPSD approaches, which are supported by the Strategy, as being effective for reducing crime. In addition, Canadians are twice as likely to select crime prevention than law enforcement as the most cost-effective way to reduce the economic and social costs of crime, and the majority rates the funding and support of local crime prevention programs in communities as a very appropriate role for the federal government. However, conclusive evidence linking the efforts of the Strategy to the generally favourable opinions of the Canadian public regarding CPSD and federal government efforts in crime prevention is not available.

Identification/Adoption of Successful Crime Prevention Approaches

The evaluation evidence suggests that the NCPS has identified a range of crime prevention approaches. Findings from the file review and document review indicate such models as: the Peer Education Model, involving youth in trouble informing others of actual and potential crimes to both prevent crime and to turn around their lives; the Drug Treatment Court, bringing law enforcement and treatment agencies together as an alternative means of dealing with drug crime; a Prevention through Education approach to reducing abuse against youth on the Internet; and encouraging youth and their parents to deal with problems together as an alternative means of counselling. In general, the involvement of multiple partners in these projects is seen as contributing to their success.

Key informants are split on how effective the NCPS has been in identifying effective crime prevention approaches. NCPC managers say the Strategy has been successful in this regard, but further success has been limited by budget cuts and high staff turnover. Regional Directors have observed an increase in the degree to which successful crime prevention approaches are being shared across regions and in the degree to which information on best crime prevention practices is being sought by schools, police agencies and health organizations. Experts too have mixed opinions: some see the Strategy’s approach as being flexible in meeting needs at the community level whereas others see the need for consideration of crime prevention approaches beyond just CPSD.

Evidence of the actual adoption of crime prevention approaches, identified and funded by the NCPS, is more limited than for the identification of such approaches.

Increased Community Capacity to Respond to Crime

The Strategy has been successful in contributing to community capacity in dealing with crime. Numerous examples were provided by key informants or identified in the document review.

As for impacts of the Strategy on knowledge development in communities, the file review suggests that most projects have in some way increased knowledge of crime prevention approaches. Key informants are generally split on this question, however. Some key informants see greater knowledge exchange across communities, while others see a lack of dissemination of NCPS research findings and insufficient use of all the knowledge that has been produced under the Strategy.

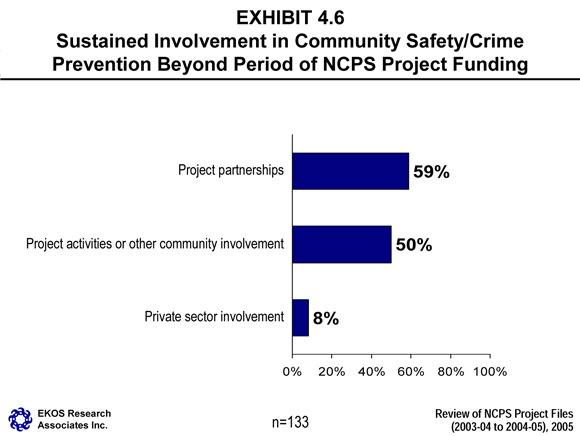

The file review indicates that in about half the projects, partnerships lasted or are expected to endure beyond the period of project funding. Similarly, the review indicates that in about half the projects, project activities or some community involvement continued after funding ended, an observation confirmed by the documentation. The sustained involvement of the private sector, however, is substantially less common.

Enhanced Policy Planning and Development in Crime Prevention

The evaluation findings suggest that the activities of the Phase II expansion have made some contribution to policy planning and development in the area of crime prevention at the federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal levels.

At the federal level, key informants highlight increased communications on crime prevention involving different departments (e.g., Canadian Heritage, Human Resources and Skills Development, the RCMP), collaboration on initiatives related to Aboriginal persons, street gangs and benefits fraud, the Strategy’s participation in 16 federal initiatives (e.g., Family Violence Initiative, Homelessness Initiative, National Drug Strategy and RCMP Youth Strategy) and advancements to policy such as the federal Aboriginal agenda as illustrations of this contribution.

Turning to the provincial and territorial government level, a similar increase in communications and collaboration between NCPC representatives and provincial/territorial officials is observed, which has in turn yielded benefits for policy planning and development (e.g., development of provincial or territorial programs modeled on the federal approach, changes in provincial youth and correctional programs, use of NCPS funds to implement crime prevention initiatives in provinces and territories).

At the municipal level, most (though not all) key informants observe that there have been policy-related benefits due, for example, to the participation of municipalities in some funded projects, exchange of information between NCPC representatives and mayors, and participation of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities. One concrete example of an influence on municipal policy comes from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside where the protocols related to the sexual exploitation of women prostitutes were altered to reflect a more restorative, proactive social development approach.

Although these contributions and improvements to information exchange have helped to improve the integration of knowledge among the three levels of government (e.g., through Comprehensive Community Initiatives, Joint Management Committee meetings, and the Vancouver Agreement), a number of key informants suggest that more work needs to be done to fully achieve such integration.

In addition, there is some evidence to indicate that the activities and outputs of the Phase II expansion have facilitated progress toward enhanced policy and programming within the NCPS. Examples include: greater collaboration between the NCPC and provinces/territories, which may lead to more informed programming (e.g., the development of a policy instrument — the Sustainability Toolkit — in cooperation with FPT Working Group members); the Centre’s “mining” studies (e.g., of anti-bullying projects) which have provided recommendations for NCPS policy on future research needs and areas of concentration for anti-bullying projects; and the increased collaboration of NCPC Regional Directors with a wider range of stakeholders.

Strengths, Weaknesses and Lessons Learned

Key informants identify an assortment of strengths, weaknesses and lessons learned about the NCPS Phase II expansion approach, but with no particular patterns by type of respondent. Partnerships are frequently identified as a strength of the NCPS, particularly in terms of involving isolated communities and organizations, especially those who would not otherwise have access to crime prevention resources. The existence of Regional Directors and other staff is considered instrumental in this regard. Additional strengths include the social development approach and the work in communities enabled by the additional funding.

Regarding weaknesses, several key informants identify challenges around the evaluation of funded projects, the paper burden associated with accountability requirements, and lack of knowledge about project results. (With respect to the dissemination of project results, however, it should be noted that the NCPC has devoted considerable effort to the mining of funded projects — related to school-based anti-bullying programs and projects for Aboriginal children and youth— and the posting of research and project results on its website.) Concerns are also raised about budget cuts and NCPC staff shortfalls, particularly as they contributed to a number of the identified weaknesses, including insufficient administrative support, reduced operating budget, uncertainty over long-term funding, and lack of a Research Director to develop a crime prevention research agenda. Another weakness cited concerns the broad-based nature of the Strategy, which increases the risk of staff losing sight of its key objectives and having difficulty focusing their efforts. Insufficient involvement of the private sector is also noted.

A number of areas for improvement concern the processing of the large amount of knowledge produced by the Strategy. Specific suggestions put forward by key informants (noting that the NCPC has been engaged in some of them) include: conducting more systematic, comprehensive research on project outcomes and on what works; and sharing best practices among communities.

Another group of suggestions concerns the image of the Strategy. Specifically in this regard, key informants suggest having a consistent crime prevention philosophy across the regions; convincing people that participating in community crime prevention activities is often more effective than simply spending on communities; and developing more communications and publication strategies such as traveling road shows.

Four main lessons learned are as follows:

The regional model of decentralized decision-making is an effective approach to funding projects that reflect the unique needs of regions and communities, but care must be taken that there are sufficient accountability controls in order to ensure that the money is spent furthering the interests of the Strategy, and not just the individual communities.

Short-term funding is not a realistic or an effective means of establishing sustained relationships and partnerships. More emphasis should be placed on long-term projects.

Attention must be paid to developing tools/templates enabling the collection of performance measurement data by project sponsors/funding recipients and entering these data into the administrative data system. Only through the collection and maintenance of such information consistently across projects can the value and impact of the Strategy be truly measured and demonstrated.

Greater effort still needs to be placed into raising public awareness of the Strategy and its successes, as a means of demonstrating the need for and value of the CPSD approach.

Recommendations

On the basis of the evaluation findings, the following recommendations are made to the NCPC:

Enhancing Performance Measurement

Continue to develop standard report templates for project sponsors to gather performance data on their projects, encouraging sponsors to gather pre- and post-project measures. Ensure that this information is entered into the administrative data system (GCIMS) so that there is real performance data in the system, and not just information on expected outcomes.

In this vein, consideration should be given to responding to the mid-term evaluation recommendation of gathering baseline data and setting measurable results targets of specified objectives of the Strategy, in order to be better able to measure performance.

Synthesizing/Disseminating Knowledge

Continue efforts to synthesize and package lessons learned and replicable models from funded projects and disseminate such information as widely as possible. Much knowledge has been developed through funded projects and commissioned research under the NCPS, and it is only through the distillation of that knowledge and its wider dissemination that the expected outcomes of adoption of crime prevention models and the eventual reduction in crime can be realized.

Ensure that more of such information is made available on the NCPS website in user-friendly forms.

Measuring Awareness and Usage

Continue efforts to raise awareness of CPSD and its potential benefits, not only via the website, but also through communications campaigns and traveling road shows.

Continue efforts to measure awareness of CPSD and measure the role played by CPSD. While past public opinion polling efforts have determined that there is a high degree of support for the concept of CPSD, no link has been made between the high awareness levels and the NCPS/NCPC. Accordingly, it is suggested that questions be incorporated into an updated public opinion poll explicitly asking respondents about their awareness of the NCPS and CPSD and the role the former may have played in awareness of the latter.

There would be merit in sponsoring a survey of law enforcement agencies to gather views on CPSD and other approaches to preventing crime.

Continue efforts to measure usage of NCPC and Strategy products. While the NCPC tracks requests for its products, it would be useful to be able to measure the degree to which the products have been found useful and have contributed to program development and increased efforts to prevent crime and ultimately to reduce crime. Towards this end, it is suggested that a pop-up survey be installed on the NCPS website to solicit the views of users with regard to the utility of the products obtained.

Increasing Private Sector Involvement

Take steps to increase the level of involvement of the private sector in crime prevention projects. For instance, develop a clear strategy and guidelines to engage the private sector, and if feasible provide additional resources for these efforts.

Managing Decentralization

While there was general support for decentralization as means of making funding more reflective of regional needs, ensure that funded projects reflect the interests of the wider Strategy.

Ensure that there is a consistent philosophy and message across the Regions in order to maintain the image of the Strategy as a national initiative.

Focusing on Strategic Long-term Project Funding

Reconsider the practice of funding large numbers of small projects as is currently done through the CMP which dominates NCPS funding, as was suggested in the mid-term evaluation. Providing small amounts of funding to numerous small communities may not be as effective a means of building up a base of knowledge and replicable models of crime prevention, as focusing funds on strategic long-term projects. Nor is short-term funding always an effective means of establishing sustained relationships and partnerships necessary for truly addressing the root causes of crime. Long-term funding of comprehensive initiatives at the community level should be given more emphasis in future project funding.

1. Introduction

This report presents the evaluation findings for the Summative Evaluation of the Phase II Expansion of the National Crime Prevention Strategy (NCPS). The NCPS is a federal initiative of the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC), designed to prevent crime and victimization in communities through the coordination of partners, facilitation of community-based solutions to crime and increased public awareness of effective social development approaches. Phase I of the Strategy was implemented in 1994, Phase II in 1998, and the expansion of Phase II in 2001. A mid-term evaluation of Phase II was conducted in the summer of 2000 and a number of recommendations were made to improve the effectiveness and delivery of the NCPS. A summative evaluation of Phase II was completed in December 2002. Later, a mid-term evaluation of the expansion of Phase II was completed in December of 2003.

1.1 The National Crime Prevention Strategy

The National Crime Prevention Strategy is based on the principle that the surest way to reduce crime is to focus on the factors that put individuals at risk. The Strategy aims to reduce crime and victimization by addressing crime before it happens. Specifically, the objectives of the NCPS are:

- to promote integrated action of key governmental and non-governmental partners to reduce crime and victimization;

- to assist communities in developing and implementing community-based solutions to crime and victimization, particularly as they affect children, youth, women and Aboriginal persons; and,

- to increase public awareness of and support for effective approaches to crime prevention.

The NCPS is based on the principle of crime prevention though social development (CPSD). CPSD is based on the philosophy that there is a need to balance law enforcement and corrections approaches to crime prevention, and to promote the reduction of victimization with social development approaches that recognize and address root causes of crime and victimization. CPSD involves identifying and addressing risk factors that are associated with criminal activity.

Risk factors include, for example, difficulties with parenting, social and economic instability, child abuse and sexual exploitation, violence, and drug/alcohol abuse. The CPSD approach provides communities with the ability to address these risk factors through social development of areas pertaining to early childhood education, parental skills training, literacy/basic skills training, and school-to-work transition programs to assist in the prevention of crime. Other areas for support include the development of capacity in communities to assist in the building of skills, knowledge and resources to identify and address risk factors. Investment in these CPSD activities is intended to build and reinforce strong communities where risk factors are present and to reduce criminal behaviour and victimization associated with these risk factors.

The CPSD philosophy is that conventional responses to crime (e.g., policing, incarceration) are not sufficient to solve issues pertaining to crime and victimization and that attention must be focused on knowledge, skills and resources around the root causes of crime and victimization.

1.2 Priority Groups of the NCPS

The NCPS is focused on four priority groups considered at particular risk with respect to crime and victimization — children, youth, Aboriginal peoples (and their communities), and women and girls.

a) Children

When provided environments that support nurturing families and a safe community environment, children are more likely to develop into law-abiding citizens that are also at a lower risk of being victims of crime. The National Crime Prevention Strategy helps communities and families to develop strategies, obtain support, and assist in reducing or eliminating known risk factors in children's lives, such as abuse, poverty, and drug and alcohol abuse.

b) Youth

Providing supports for youth addresses risk factors related to the underlying causes of crime and victimization, such as child abuse, difficulties with parenting, social isolation, uncontrolled anger, bullying behaviour and poor academic achievement. Research by Statistics Canada (2003) 2 indicates that children subjected to risk factors, such as those noted above, are at higher risk of inappropriate behaviours that may later manifest as criminal offences as adults.

Establishing high quality relationships with adults and peers is seen as an effective way of reducing the risk of crime among children and youth exposed to these risk factors.4

c) Aboriginal Peoples

Aboriginal peoples experience disproportionately higher rates of violence, victimization and poverty than non-Aboriginal communities. Reflecting the NCPS’s particular niche, the National Crime Prevention Centre (the organization responsible for the delivery of the NCPS) focuses on crime prevention through social development in Aboriginal communities. The NCPC conducts its work in partnership with others to provide a comprehensive response to the needs of Aboriginal people.

d) Personal Security of Women and Girls

Research indicates that one half of Canadian women have reported at least one incident of violence since the age of 16 (Statistics Canada, 1993).6 Crime and the pervading fear of crime prevent women from fully participating in community life, employment and education, and reinforce gender inequality.

e) Other Groups

In addition, the NCPS has broadened its work to address other at-risk groups. These groups are as follows:

- Seniors: Limited mobility and dependence on others can cause the elderly to be victimized by crime. Seniors are often victims of fraud and other forms of financial abuse, and fear of crime is highest among this population group. Seniors are generally much less likely than people in younger age groups to be the victims of a crime, although they are more likely than younger people to feel vulnerable when outside their homes.

- Ethno-cultural Groups: Multiculturalism is one of Canada's strengths. Yet sadly, racism and cultural prejudice still persist in many areas. The National Crime Prevention Strategy supports projects that create tolerance and understanding of different cultures and ethnicities.

- Gay and Lesbian People: Homophobia continues to be a serious problem in Canada. The mistreatment of homosexual Canadians occurs in many ways and limits this population's ability to live freely in society.

- Persons with Disabilities: This population group is victimized by crime at a disproportionate rate, due to limitations in mobility and dependence on others. The National Crime Prevention Strategy is committed to finding ways of empowering persons with disabilities to help them avoid situations of risk.

1.3 Phase I of the National Crime Prevention Strategy

The Government of Canada launched Phase I of the National Strategy on Community Safety and Crime Prevention in 1994 (which was renamed the National Crime Prevention Strategy in 2002). It provided a framework for federal efforts to support community safety and crime prevention, encouraged federal, provincial and territorial cooperation, and emphasized the mobilization of Canadians to take action at the community level to prevent crime.

Phase I involved the creation of the National Crime Prevention Council (1994-1997), made up of 25 individuals that included child development experts, community advocates, academics, social workers, lawyers, police officers, doctors, and business people who volunteered their time to develop a plan to deal with the underlying causes of crime.

Promoting CPSD, the former Council focused on children and youth and developed models for dealing with the early prevention of criminal behaviour. These models showed that children need adequate care throughout their early lives, even while they are in the womb. Above all else, children need good parenting. At the same time, there is a need to eliminate, to the extent possible, known risk factors in children's lives, such as abuse, poverty, and drug and alcohol abuse (NCPC, 2004).7

1.4 Phase II of the National Crime Prevention Strategy

In 1998, Phase II of the National Crime Prevention Strategy was launched with Barbara Hall as the acting chair of the Strategy from 1998-2002. With an initial investment of $32 million per year, Phase II has enabled broadened partnerships and aid to communities that has designed and implemented innovative and sustainable ways to prevent crime and victimization.

Building on the work of the National Crime Prevention Council, Phase II of the NCPS aims to increase individual and community safety by equipping Canadians with the knowledge, skills, and resources they need to advance crime prevention efforts in their communities. The overall objectives of Phase II are as follows:

- to promote partnerships between governments, businesses, community groups, and individuals to reduce crime and victimization;

- to assist communities in developing and implementing community-based solutions to local problems that contribute to crime and victimization;

- to increase public awareness of, and support for, crime prevention; and,

- to conduct research on crime prevention and establish best practices.

1.5 Phase II Expansion of the National Crime Prevention Strategy

In May 2001, the federal government announced the expansion of Phase II. At that time, the NCPS was comprised of three components – the National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC), the Safer Communities Initiative, and Promotion and Public Education. Two major changes occurred as a result of the expansion: the implementation of a fifth Safer Communities funding program, the Crime Prevention Strategic Fund (SF or Strategic Fund); and the implementation of an additional component to the Strategy, the Crime Prevention and Public Safety Initiative (CPPSI).

The expansion of Phase II also included an additional investment of $145 million over four years (2001-2005). This additional funding was to provide more support for community projects, a strengthened infrastructure, and greater reach into every part of the country. The rationale underlying such a strategic investment is to reduce the burden of the traditional criminal justice system on taxpayers by stopping crimes before they occur. More specifically, the expansion was to allow the NCPS to do the following:

- undertake the development work required to make a difference in high-need, low-capacity communities, including inner-city, rural, remote, and Aboriginal communities;

- offer a continuum of supports and crime prevention models for communities that require a range of programming interventions;

- facilitate citizen engagement through broad and enduring public education efforts and informed discussion, again with an emphasis on high-risk, high-needs/low-capacity communities, and with a focus on sharing the best practices and success stories that can spur like-minded initiatives;

- expand the scope of relationships with non-traditional partners and deepen the range of efforts to priority areas, such as seniors and persons with disabilities; and

- establish a centre of excellence, expertise, and learn to work on crime prevention projects, research, policy, and practice (NCPS, 2004).8

Over the course of the Phase II expansion, a variety of departmental and organizational changes have occurred. For instance, the NCPS and NCPC were originally under the direction of the Department of Justice, and later changed to the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC) during a reorganization of certain federal government departments. Furthermore, prior to the transfer of the Strategy from Justice to PSEPC, there was a hiring freeze the last two years while the Strategy was under the Department of Justice. In addition, NCPC has seen two Executive Directors come and go over the course of the expansion, and a third Executive Director came into the position in April 2005.

1.6 NCPS Programs

The overall program design of the NCPS is reflected in the four key components including the National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC), the Safer Communities Initiative, the Promotion and Public Education Program (&PE), and the Crime Prevention and Public Safety Initiative (CPPSI).

a) National Crime Prevention Centre

First, the National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC) is responsible for overall management and implementation of the NCPS and is the principal administrator of the NCPS. The NCPC activities include policy and strategic planning, coordination of activities within the federal government and between the federal and provincial/territorial governments, research and evaluation, and administration of funding programs (under the Safer Communities Initiative). Overall responsibility for the Centre rests with the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada.

The NCPC serves as the federal government’s crime prevention policy centre. Though housed within the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, the NCPC is a separate organizational unit with its own funds administration.

b) Safer Communities Initiative Funding Programs

The second component of the NCPS, the Safer Communities Initiative, is administered by the NCPC and consists of grants and contributions funding programs. The Safer Communities Initiative is designed to assist Canadians in undertaking crime prevention activities in their communities through the development and implementation of programs — the Community Mobilization Program (CMP), the Crime Prevention Partnership Program (CPPP), the Business Action Program on Crime Prevention (BAP), the Crime Prevention Investment Fund (CPIF), and the Crime Prevention Strategic Fund (SF). These programs fund communities and organizations to develop, implement and evaluate CPSD models. All of these programs are overseen by a Director, Program Development and Delivery who then reports directly to the NCPC Executive Director.

Community Mobilization Program (CMP)9

The CMP helps communities develop comprehensive and sustainable approaches to crime prevention and undertake activities that deal with the root causes of crime in their communities.

The objectives of the CMP are as follows:

- To increase the development of broad, community-based partnerships focused on dealing with local crime prevention issues;

- To increase public awareness of and support for crime prevention at the local level; and

- To increase the capacity of diverse communities to deal with crime and victimization.

The CMP is intended to complement activities that are already under way within communities in every province and territory. To do this effectively, the NCPC has established a Joint Management Committee in each jurisdiction. Membership on this committee varies from one jurisdiction to the next, but usually includes representatives of the provincial or territorial government, the federal government, and other partners and/or community members who share an interest in crime prevention.

The CMP is not intended to duplicate or replace work already taking place in communities. Rather, the CMP invests in people and communities by building on government, voluntary, and private sector initiatives.

To prevent crime and victimization effectively, each community has to identify its assets and needs. Communities also have to mobilize a variety of players, including those providing services in areas such as housing, social services, public health, policing, community sports and recreation, schools, and other socio-cultural organizations such as those serving women, children, or youth.

Communities may need support to undertake a wide range of activities, including the assessment of their assets, capacity, and needs; planning; training; the dissemination of information; skills building; conflict resolution; consensus building; and the evaluation of crime prevention initiatives.

To qualify for CMP funding, these activities must be based on collaborative approaches that have clear objectives and measurable results using a crime prevention through social development approach.

Crime Prevention Partnership Program (CPPP) 10

The CPPP aims to support the involvement of organizations that can contribute to community crime prevention activities through the development and dissemination of information, tools, and resources that assist in community participation in all phases of crime prevention. These tools and resources can consist of needs assessments, development of plans, implementation and evaluation that can be used across the country.

While national in scope, to ensure program flexibility and the ability to respond to issues identified at the regional level, the CPPP can consider projects that are regionally based.

The objectives of the CPPP are to:

Support the development of information, tools and resources for communities to use in implementing community-based crime prevention solutions;

Encourage organizations to enhance networks at the national, regional, and local levels in order to develop, share and build on tools and resources available to communities;

Inform and enhance community-based crime prevention initiatives through the dissemination of crime prevention tools and resources developed by other communities of interest across Canada; and

Build strong and integrated national partnerships between organizations and others across Canada working to implement crime prevention initiatives.

Business Action Program on Crime Prevention (BAP) 11

The BAP invites the private sector to become an active partner, leader, and resource in crime prevention. The networks of private sector organizations throughout Canada can help communities prevent crime, share information, and encourage community mobilization.

The objectives of the BAP are to:

- Engage the private sector as active partners, leaders, and resources on crime prevention within communities; and,

- Raise public awareness about crime prevention.

The BAP is guided by the Business Network on Crime Prevention (BNCP), a group of professional associations working together to build safer communities. The BNCP meets as needed to review project proposals and recommend them for approval to PSEPC. Although still in operation, the BNCP has not been very active recently because there have been no solicitations of BAP proposals in the last two years by design.

A key objective of the BNCP is promoting the involvement of the private sector in contributing to the reduction of crime and victimization in communities across Canada. Using the BAP, the BNCP works through business and professional associations to:

- Raise awareness about the advantages of early intervention with children and youth to reduce their possible involvement in criminal behaviour;

- Strengthen business-community partnerships to develop sustainable approaches to reducing crime and victimization;

- Stimulate coordinated efforts to address crime prevention issues of particular concern to the private sector; and

- Develop tools and resources to help the private sector better understand what works best to reduce crime and victimization.

The three organizational components of BAP are:

- the grant funding program itself;

- the Business Network on Crime Prevention (BNCP), formerly the Business Alliance on Crime Prevention, which is composed of representatives of national business organizations, promotes partnerships on crime prevention, and recommends projects for BAP funding; and,

- a mini-secretariat that administers the Program and provides support to the BNCP.

Crime Prevention Investment Fund (CPIF) 12

The CPIF supports promising and innovative crime prevention through social development demonstration projects in high-need areas across the country. Support for the implementation and independent evaluation of these programs is aimed at determining the key components of successful programs and the potential for these new approaches to be replicated in other settings across the country.

The objectives of the CPIF are to:

- Identify and support promising and innovative, community-based crime prevention models in high-need and under-resourced communities and population groups;

- Conduct independent evaluations of these models to determine the key components of successful programs and the extent to which they can be replicated in other settings across the country;

- Share information on high-quality crime prevention projects that are community-based, multidisciplinary, cost-effective and sustainable; and

- Promote long-term savings by building on best practices in crime prevention to achieve an integrated, cost-effective approach to crime prevention through social development.

The CPIF responds to the need to fill knowledge gaps about the key elements of effective social development approaches to the prevention of crime and victimization in Canada. The CPIF demonstration projects already underway are serving to increase our understanding of the impact and effectiveness of community-based social development strategies that support the specific needs of children, families, and communities at risk of crime and victimization.

The fiscal year 2001-2002 marked the beginning of Cycle II of CPIF funding activity under the National Crime Prevention Strategy. Distinct from Cycle I, this second cycle gives special attention to proposals focusing on selected regions of the country according to predetermined priorities. These priorities were established through consultations with federal, provincial, and territorial partners and stakeholders across the country.

Successful applicants are awarded contribution funding for a period of three to five years, not exceeding $500,000 per year (most projects receive funding for less than the maximum period and amount). Once a demonstration project has been approved for funding under the CPIF, a Request for Proposals (RFP) is issued to solicit proposals from third parties for an independent evaluation. Each demonstration project supported by the CPIF must undergo a rigorous process and outcome evaluation, including the development of a theory of change model and the collection of project costing data, carried out by independent third-party researchers contracted directly by the NCPC.

Crime Prevention Strategic Fund (SF)

The Crime Prevention Strategic Fund (SF), a fifth Safer Communities funding program, is designed to support pilot projects that demonstrate the movement from independent and sometimes isolated crime prevention projects to more strategic broad strategies that will contribute to knowledge and action on sustainable crime prevention through social development; to support crime prevention activities that fall between the other four funding programs; and to facilitate, at the community level, the horizontal management of crime prevention initiatives among other federal departments, with other federal initiatives and with other levels of government.

Project Funding Levels for Safer Communities Programs

Administrative data on the funding levels for projects under the five Safer Communities programs over the four years of the NCPS Phase II expansion period are presented in Table 1.1. CMP projects have clearly played a dominant role in the Phase II expansion, accounting for 89 per cent of all funded projects and 53 per cent of all funding dollars. The average funding amount for CMP projects was the smallest of all five programs – just $33,005. CPIF projects are also noteworthy due to their large funding amounts (an average of $530,263 per project) – accounting for 25 per cent of all funding.

A regional breakdown of project funding for the Phase II expansion period is provided in Table 1.2. The project activity appears to be roughly proportional to the population in each region. Most project activity under the five Safer Communities programs has taken place in Ontario (which was allocated 27 per cent of all projects and 32 per cent of all funding) and Quebec (23 and 24 per cent, respectively). On the other hand, the lowest level of project activity was in the Northern Region – five per cent of all projects and four per cent of all funding.

Table 1.1 Project Funding Levels by Program

(Projects Started or Ended May 2001 – March 2005)

| Program | Number of Projects | Distribution of Projects (%) | Average Funding Committed per Project | Distribution of Funding (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMP | 2,320 | 89 | $33,005 | 53 |

| BAP | 67 | 3 | $112,562 | 5 |

| CPIF | 69 | 3 | $530,263 | 25 |

| CPPP | 132 | 5 | $146,304 | 13 |

| SF | 31 | 1 | $174,476 | 4 |

| Total | 2,619 | 100 | $55,525 | 100 |

Source: Project Control System data, as of March 2005.

Table 1.2 Project Funding Levels by Region

(Projects Started or Ended May 2001 – March 2005)

| Region | Number of Projects | Distribution of Projects (%) | Average Funding Committed per Project | Distribution of Funding (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic | 443 | 17 | $36,470 | 11 |

| Quebec | 609 | 23 | $56,637 | 24 |

| Ontario | 709 | 27 | $64,592 | 32 |

| Prairies | 401 | 15 | $56,746 | 16 |

| BC | 331 | 13 | $61,353 | 14 |

| Northern | 126 | 5 | $46,942 | 4 |

| Total | 2,619 | 100 | $55,525 | 100 |

Source: Project Control System data, as of March 2005.

c) Promotion and Public Education Program

The third major component of the NCPS is the Promotion and Public Education Program (PPEP). The Promotion and Public Education Program has been created to increase public awareness about the National Crime Prevention Strategy. It has the following goals:

- To promote an understanding of CPSD;

- To provide a better understanding of crime and victimization issues in Canada;

- To foster partnerships with organizations to create and disseminate innovative approaches to preventing crime;

- To share crime prevention success stories, tools, knowledge, and information with Canadians; and,

- To empower Canadians to seek and develop solutions to problems in their own communities.

The Communications, Promotion, and Public Education Team coordinates the Promotion and Public Education Program and is responsible for media relations, public events and announcements, the production and distribution of NCPS publications and multimedia tools, the NCPS Web site, and the resource centre.

d) Crime Prevention and Public Safety Initiative

The CPPSI is in place to strengthen and build capacity in the areas of policing and corrections to address the root causes of crime. To attain this objective, the implementation of four crime prevention and public safety related elements will support innovative initiatives that will work to build capacity and address particular issues that need greater attention. These include crime and victimization issues in Aboriginal and remote/isolated communities, substance abuse awareness and prevention, addressing the risks associated with children and families of offenders, and developing strategies to deal with youth at risk.

1.7 Purpose and Organization of the Report

The purpose of this report is to present the evaluation findings and conclusions, based on the key informant interviews, project file review, administrative data review and documentation review conducted for the evaluation of the NCPS Phase II expansion. In Chapter Two, the evaluation context, objectives and issues are presented. Then, the evaluation methodology is described in Chapter Three. The evaluation findings related to each issue are presented in Chapter Four. Finally, the conclusions and recommendations are presented in Chapter Five.

2. Evaluation Objectives and Issues

2.1 Evaluation Objectives and Context

The overall objective of this evaluation was to support PSEPC’s inherited commitment to accountability for and evaluation of the expansion of Phase II of the NCPS. The evaluation focused on the achievements of the former Department of Justice component of the expansion of Phase II. The scope of the evaluation included the four years of the Phase II expansion (2001-02 to 2004-05) and all NCPS programs, with the exception of the Crime Prevention and Public Safety Initiative (CPPSI), which was evaluated separately as this was the responsibility of the former Solicitor General of Canada.

The evaluation primarily addressed success and achievement issues, given that the mid-term evaluation concentrated on design and delivery issues. The focus was on impacts, in particular, on what has been accomplished since the mid-term evaluation. In addition, the evaluation assessed the strengths and weaknesses, challenges faced and lessons learned by the NCPS, and provided recommendations related to the renewal of the Strategy.

It should be noted as context that the NCPC has faced a variety of operational challenges, which have caused delays and hampered the implementation of the Phase II expansion of the NCPS. These challenges have included: overworked staff for the past two years due to budgetary constraints on staffing; the lack of a Director, Research and Evaluation for the past two years (the position has been vacant); and an overall climate of uncertainty as to the future of the NCPS, including the uncertainty associated with the end of the expansion sunset funding, which has led to high staff turnover. Moreover, the NCPS and the NCPC have shifted from the Department of Justice to the new Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC). The transition and adjustment to a new organizational environment and departmental culture clearly takes time. In assessing the progress and impacts of the Phase II expansion, these factors needed to be taken into account.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

The summative evaluation of the expansion of Phase II focused on assessing the degree to which the expansion has made progress toward and achieved its objectives/intended outcomes. A matrix linking the evaluation issues/questions with indicators and data sources/methods is provided in Appendix A.

The evaluation issues/questions are as follows:

Broader Participation in Crime Prevention:

To what extent has the expansion of the NCPS Phase II resulted in broader participation in community safety and crime prevention initiatives by:

- non-governmental organizations and community groups;

- the private sector;

- municipalities;

- police and community corrections; and

- high-risk communities?

- In what ways has the involvement of these groups contributed to the achievement of the objectives of the NCPS expansion?

Increased Awareness/Understanding of Crime Prevention:

- To what extent has the expansion of the NCPS increased public, stakeholder and partner understanding of community safety and crime prevention?

Identification/Adoption of Successful Crime Prevention Approaches:

- To what extent has the expansion contributed to the successful identification and adoption of effective approaches to crime prevention?

Increased Community Capacity to Respond to Crime:

- To what extent has the expansion of the NCPS contributed to community capacity to respond to local crime and victimization?

Enhanced Policy Planning and Development in Crime Prevention:

- To what extent have the activities of the expansion contributed to policy planning and development in the area of crime prevention at the federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal levels?

- To what extent have these activities resulted in (or facilitated progress towards) enhanced policy and programming within the NCPS?

Strengths and Weaknesses:

- What have been the strengths and weaknesses of the NCPS approach taken to support the federal involvement in crime prevention and community safety?

Lessons Learned:

- What lessons have been learned as a result of the expansion of the NCPS Phase II?

3. Methodology

3.1 Overview

The evaluation issues/questions presented in the previous chapter were examined through the collection and analysis of information from the following sources/methods:

- Review of program and related documentation and project files (n=133);

- Review of administrative data to provide a descriptive analysis of the Strategy; and

- Key informant interviews (n=20) with NCPC managers at the Ottawa office, NCPC Regional Directors, key Strategy partners, and external experts in community safety and crime prevention.

A matrix linking the evaluation issues with indicators and data sources/methods is provided in Appendix A. The data collection instruments are provided in a separate document. The methodological approach for the evaluation is described in detail in the remainder of this chapter.

3.2 Document and File Review

The work on this component of the evaluation was divided between a review of NCPS documentation (e.g., background documentation, recent internal and external studies, and consultation materials) and individual project files. As significant work had already been done (e.g., in recent audits) regarding the effectiveness of processes and resources for project development, implementation and monitoring, this type of data collection was not repeated in the present evaluation. Still, there was a need to gather some information related to the evaluation issues in a file review.

a) Review of Documentation

A complete list of the documents reviewed is provided in Appendix B. The review included the following types of documentation:

- Previous evaluations/audits: These documents include reports on the Summative Evaluation of Phase II (2003), the Mid-term Evaluation of the Expansion of Phase II (2004), and the NCPC Audit (2004).

- National documents: These documents consist of a variety of files, including media announcements and news releases, internal reports, professional correspondence, and reports on strategic priorities as well as products created by the NCPC for education on the Strategy and CPSD.

- Regional documents: These documents primarily pertain to funded projects for each Region and also include training packages, presentation decks on CPSD and proposal writing, and general summaries of funded projects.

- Policy Development, Strategic Planning and Research Unit documents: These research-related documents include government and academic publications.

- Additional documentation: This documentation includes evaluation materials (training packages and funding stream evaluation templates), the Performance Report for the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (for the period ending March 31, 2004), media clippings and internal government news reports.

In addition, in conjunction with interviews conducted with NCPC Regional Directors, documentation on successful and innovative projects (highlighted by the Regional Directors) in each Region was reviewed in a qualitative fashion. An examination of documentation on these projects, coupled with the interview and questionnaire responses of Regional Directors (see Appendix E), provided information on successful/innovative projects and best practices in each Region.

b) Project File Review

The overall objective of the project file review was to obtain information on a range of projects in order to provide a greater understanding of NCPS implementation, reach and impacts. A representative sample of 133 project files 13 with Final Reports was reviewed on-site at the NCPC. Data on each project were entered online into an electronic version of the file review guide. The 133 projects selected for review were as follows:

- CMP projects (n=109): Of 202 CMP projects from 2003-2004 and 2004-2005 for which Final Reports had been submitted (as of February 1, 2005), a random sample of 109 projects – with the regional proportions in the sample the same as those in the population of 202 projects — was reviewed.

- CPIF, CPPP, BAP and SF projects (n=24): Of 29 funded projects from these other four programs that started during the Phase II expansion period and for which Final Reports had been submitted in 2003-2004 or 2004-2005 (as of February 1, 2005), a sample of 24 projects was reviewed.

Aside from a Final Report or evaluation report/template, a number of the files also included other useful information such as financial statements (76 per cent or files), letters of support (74 per cent), tools/resources developed (49 per cent), and news articles (26 per cent). Virtually all of the project reports included some anecdotal data/evidence related to project outputs or outcomes (99 per cent), and some also reported some qualitative or quantitative data (29 per cent and 18 per cent, respectively).

Data collected in the review of project files were both quantitative and qualitative, depending on the nature of the indicators. Quantitative and qualitative analyses of these data were carried out as appropriate.

3.3 Administrative Data Review

A review of administrative data was also conducted, utilizing program/project delivery data from the Project Control System (PCS). This component of the evaluation provided a descriptive analysis of the Strategy and some evidence on the types of partners participating in and groups affected by funded projects. Specifically, the data enabled us to measure total and per-project average funding levels for the Safer Communities funding programs, their province/Region, project activities, the types of partner organizations, as well as the priority groups addressed by these projects. The focus was on projects funded during the Phase II expansion timeframe (2001-2002 to 2004-2005). Tables of administrative data are provided in Appendix C.

3.4 Key Informant Interviews

Interviews with 20 key informants were conducted, including NCPC Ottawa office managers, NCPC Regional Directors, key Strategy partners, and external experts in community safety and crime prevention (e.g., academic researchers in the field). Specific contacts and the distribution of these 20 interviews were determined in consultation with the Project Authority and Summative Evaluation Advisory Committee. The interviewees are listed in Appendix D.

A bilingual letter of introduction was used when contacting each potential interview respondent. This letter briefly introduced the evaluation and provided a contact number for anyone who wished to verify the legitimacy of the interviews. The executive summary of the mid-term evaluation of the NCPS Phase II expansion was sent as background with the letters.

Semi-structured interview guides, tailored to the different groups of key informants, were utilized for the key informant interviews. All groups of key informants were asked for their views on all of the evaluation issues, with the exception of the external experts who were questioned only about the overall success of the NCPS approach, the identification and adoptation of successful crime prevention approaches, and the Strategy’s strengths, weaknesses, and lessons learned.

Each interview lasted approximately 60 minutes, though interviews with Regional Directors were more in-depth, lasting 90 to 120 minutes. In addition, the Regional Directors were first sent a brief questionnaire (e.g., asking them to specify what has been going on in their Region that supports the Strategy’s objectives) and asked to provide written responses. Their responses provided important details and examples of NCPS initiatives in all regions across the country (see Appendix E for a summary of these responses). In the subsequent key informant interviews, the Regional Directors were asked to elaborate on their written responses as well as respond to the formal interview questions.

A copy of the introductory letter, background material and interview guide were sent to all key informants in advance of their interview, to provide them with an opportunity to prepare for the interview. Interviews were conducted by phone or in-person (if desired, by key informants in the National Capital Region). All key informants were interviewed in the official language of their choice.

Summaries of the individual interviews were prepared for internal use following each interview and organized by evaluation question for purposes of analysis.

3.5 Integrated Analysis

Following the completion of all data collection for the evaluation of the NCPS Phase II expansion, the results of each methodological component were analyzed. The findings from the various lines of evidence were then integrated and organized by the evaluation issues. In the integrated analysis, the evidence from different sources was triangulated to identify the issues on which the evaluation findings converged and also to help reconcile any incomplete or contradictory findings. The integrated evaluation findings are presented in Chapter Four.

4. Findings

4.1 Broader Participation in Crime Prevention

a) Broader Participation of Stakeholders

Overview: The extent to which the NCPS Phase II expansion has resulted in broader participation in community safety and crime prevention initiatives by various stakeholder groups is addressed in this section. Evaluation findings from the key informant interviews and review of documentation, administrative data and project files indicate that the Phase II expansion has helped to broaden the participation of non-governmental organizations, community groups, the police and high-risk communities, but there have been lower levels of participation by community correctional agencies and the private sector. The comparatively low level of participation from community corrections is not necessarily a negative finding, given that this stakeholder group is a primary focus of the CPPSI component of the Strategy, which was not examined in this evaluation. Regarding the participation of municipalities (beyond municipal police agencies), the evaluation findings are mixed suggesting that municipal involvement has not been uniformly strong in all areas of the country (e.g., regional/municipal government partners are least common in the Northern Region). Still, there are numerous examples of relevant participation by some municipalities. More detailed findings are presented below.

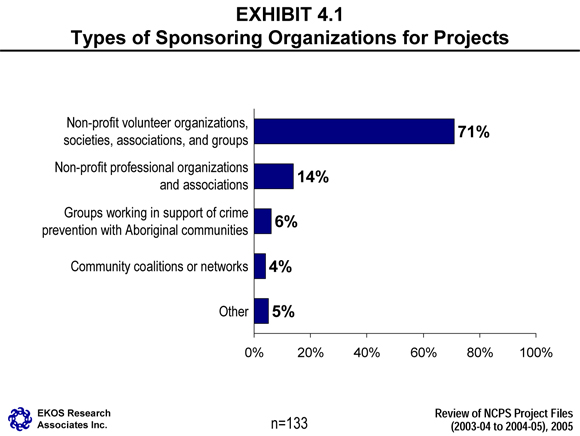

The project file review provides an overall indication of the types of participants in funded projects, including the sponsoring organizations, project partners and priority groups served. As illustrated in Exhibit 4.1, project sponsors are most often non-profit volunteer organizations, associations, etc. (71 per cent) or non-profit professional organizations/associations (14 per cent). Regarding the specific sector of project sponsors, these organizations are most frequently from social services (79 per cent), education (30 per cent), health (20 per cent), crime prevention (19 per cent), or housing services (11 per cent). Among the projects reviewed, very few sponsors were from the business sector (seven per cent), though only eight BAP projects were included in the file review sample.

Partnerships that have been formed are wide ranging, with the top five types of organizations being provincial/territorial governments (46 per cent), regional/municipal governments (44 per cent), nongovernmental organizations (42 per cent), non-profit organizations (31 per cent), and private enterprises (24 per cent). In addition, in a notable proportion of the projects reviewed, partnerships were formed with the federal government (22 per cent), individuals (21 per cent), associations (15 per cent), band/tribal councils (14 per cent) and communities (11 per cent).

While in-kind (94 per cent) and financial contributions (80 per cent) are most common, project partners also contribute with networking and mobilization to assist with community safety and crime prevention issues (38 per cent), and networking to help disseminate information, tools and resources (38 per cent). These file review findings are illustrated in Exhibit 4.2.

In the file review sample, the average value of funding from Strategy programs is $44,229 and the average value of in-kind/financial contributions amounts to $67,288. These contributions/funds (i.e., beyond those provided by NCPS programs) primarily come from non-governmental organizations (47 per cent), provincial/territorial (44 per cent) and municipal governments (39 per cent). Non-profit organizations (29 per cent) and private enterprises (23 per cent) round off the top five sources of additional funding.

To supplement the project file review, an analysis was conduced of administrative data from the NCPC’s Project Control System (PCS) database, which provides a comprehensive profile of the types of partners/contributors for all projects funded under the five Strategy programs for full the Phase II expansion period (May 2001 to March 2005). As indicated in Table 4.1 below, and generally consistent with the file review findings, the major types of contributing partners are as follows: