Evaluation of the First Nations Policing Program 2014-15

Table of contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Profile

- 3. About the Evaluation

- 3.1 Objective

- 3.2 Scope

- 3.3 Methodology

- 3.4 Limitations

- 3.5 Protocols

- 4. Findings

- 5. Conclusions

- 6. Recommendations

- 7. Management Responses and Action Plan

- Appendix A: Documents Reviewed

Executive Summary

Evaluation supports accountability to Parliament and Canadians by helping the Government of Canada to credibly report on the results achieved with resources invested in programs. Evaluation supports deputy heads in managing for results by informing them about whether their programs are producing the outcomes that they were designed to achieve, at an affordable cost, and supports policy and program improvements by helping to identify lessons learned and best practices.

What we examined

The evaluation assessed the relevance and performance of the First Nations Policing Program (FNPP)Note 1. The evaluation team reviewed earlier studies that focused on administrative aspects of the program and gathered new data to examine the FNPP's policy response, funding model, and alternative delivery approaches.

Why it is important

Crime rates in First Nations (FNs) and Inuit communities remain higher than in the rest of Canada. Crime and disorder have a corrosive impact upon community well-being and quality of life. High rates of crime and victimization are costly to communities both in terms of tangible costs and intangible costs such as lost quality of life resulting from psychological effects of victimization.

What we found

Relevance

A program that addresses safety and security in FNs and Inuit communities remains relevant and necessary. From 2004 to 2013, the overall volume of crime in FNPP communities declined as it did in the rest of Canada. However, the incidents of crime on-reserve still remained almost four times higher, and incidents of violent crime were about six times higher than the rest of Canada. Risk factors of offending and victimization are higher among the Aboriginal population. Statistics Canada data from 2011 demonstrates that Aboriginals had lower educational achievement and were economically disadvantaged. About one-third of Aboriginal children lived in a lone-parent family compared with about one in five non-Aboriginal children, and Aboriginals were far more likely than other Canadians to be victims of violence. In this broader social context, policing is not the sole answer to reducing crime in FNs and Inuit communities.

In terms of roles and responsibilities, all levels of government and communities themselves have a role to play in the FNPP. The Government of Canada has a role in coordinating police services in FNs and Inuit communities. However, it is important that communities are engaged in order to participate in setting policing priorities and negotiating agreements. Policing should be planned and managed primarily at the provincial/territorial level as it is this level of government that is responsible for general policing and policing standards.

Due to its role in keeping communities safe and secure, Public Safety Canada is the federal department best suited to play a coordination role for the FNPP. It is also well suited to maintain linkages to other federal investments in FNs and Inuit communities in the area of health, education, social services and economic development.

Performance

Evidence shows that community engagement is essential for successful program administration, design and delivery. FNs and Inuit communities need to be engaged, own the program and set the pace. These notions are stated in the overarching policy objectives of the FNPP. The policy objectives focus on providing policing services that are responsive to the needs of communities, and on supporting communities in acquiring tools for increased responsibility and accountability. Under the policy, Public Safety Canada was to implement and administer the FNPP in a manner that promoted partnerships based on trust, mutual respect, and participation in decision-making. The evaluation found that the Program has not sufficiently engaged communities so as to enable success of the program against these overarching objectives. This finding is pervasive.

Although the FNPP has made a difference in funded communities, gaps persist as the program is not accessible to all communities. In 2013-14, the program was in place in close to 60% of the 688 FNs and Inuit communitiesNote 2 in Canada. The evaluation acknowledges that funding has been frozen since 2007, leaving little opportunity to expand the program into remaining communities. Interviews and document review indicate that reallocation of resources would be challenging because funding decisions are based on the historical footprint and on the availability of funding. In addition, there is a lack of community-based needs information, and historically, there was no systematic approach for the funding allocations. Given these factors, the evaluation team could not determine if the existing funding envelope could be used to expand the program into remaining communities to address the gap.

Under the FNPP, community members are expected to play a role through police governing boards or advisory bodies. These organizations are meant to enable communities to participate in setting policing priorities. The evaluation found that 60% of funded communities have governing structures in place. While this result is better than non-FNPP communities, interviews and document review noted that communities require more meaningful input into policing priorities and agreements. Communities indicated that final agreements were sometimes presented for their approval with little or no prior engagement or consultation. Further work in this area would promote increased responsibility and accountability in communities.

The evaluation notes that most stakeholders have focused on the achievement of objectives included in the program's Terms and Conditions (T&C objectives). Few stakeholders were aware of the overarching policy objectives. The T&C objectives indicate that policing in FN and Inuit communities should be responsiveNote 3, professionalNote 4 and dedicatedNote 5 to communities where they serve.

Community members perceive that responsiveness of police officers has improved in both self-administered agreement (SA) and community tripartite agreement (CTA) communities. Interviewees in communities with SAs were satisfied with the cultural responsiveness of police officers noting the key advantage having officers embedded in the community. As well, 86% of the CTA communities that responded to a questionnaireNote 6 indicated that police services are being delivered in a manner that is respectful of their culture.

However, the evaluation found differences in the amount of time that police services dedicated to the communities. A high percentage (85%) of officers funded under SAs who responded to a questionnaireNote 7 indicated that they are dedicated to the communities. This compares to 53% of officer respondents from CTAs. In many CTA communities, the intent of having dedicated FNPP officers has been eroded because officers are not embedded in the communities. Police are spending their time getting to and from communities, or on other policing priorities rather than on FNPP activities.

With regards to professionalism, police services funded by FNPP are meeting provincial policing policies and standards. However, officers working under SAs have limited access to ongoing training and limited resources for job related tools, compared to police officers working under CTAs.

The evaluation found that contribution agreements are not the ideal delivery mechanism for FNPP. This was also noted in the 2010 evaluation and the 2014 Office of the Auditor General report. Contribution agreements require frequent renewals and there is a heavy administrative burden associated with each renewal. This factor and funding uncertainty precludes communities and police services from conducting long-term forward planning.

In terms of alternative delivery approaches, few best practices associated with Aboriginal policing have been identified. However, literature review reveals that an approach can only be successful if communities become full partners and take ownership of the solution. Through implementation of several pilot projects, Public Safety Canada has explored innovative approaches to address the increasing cost of policing and to offer better community engagement. These approaches include the principles found in recent studies of economics of policing and integrate a more holistic, community-based solution into existing programming.

Under a tiered policingNote 8 approach, the File Hills Constable Pilot Project (Saskatchewan) was implemented in an FNPP community within an existing SA agreement. The project includes five Special Constables, hired from the community, that provide support to policing functions such as community outreach and public information presentations. The constables maintain a level of policing that is culturally sensitive and that enhances public safety. It is noted that in order for this approach to succeed, there is a need for high functioning community governance and strong community-based support.

In terms of wider alternatives, evidence shows that there is a need for a horizontal approach to address FNs and Inuit issues that involves all partners at the federal, provincial and community levels. Government agencies with mandates such as health, education, employment, justice, and corrections should be involved. Participation from FNs and Inuit communities is necessary. The evaluation identified the need for the Federal Government to stop working in silos and address FNs and Inuit issues from a holistic perspective.

Two Public Safety Canada pilot projects explore this type of multi-agency approach to social issues. These are the Prince Albert HUB Model and Social Navigator. The HUB is not about policing but rather a community safety approach. It involves evidence-based collaborative problem solving that draws on the combined expertise of relevant community agencies to address complex human and social problems before they become policing problems. The HUB approach has been found to enhance collaboration and communication between police and other community agencies and assist in mitigating acutely elevated risk of harm or victimization.Note 9

The Social Navigator approach refers at risk individuals who have had repeated encounters with the police to the appropriate service provider based on their individual needs. The goal is to keep that individual out of the criminal justice system. The social navigator's role is to maintain cultural practices and understanding while addressing the full spectrum of crime reduction. The social navigator pilot was underway at the time of the evaluation.

Public Safety Canada's Aboriginal Community Safety Development Program has advanced other efforts for community-based planning in 16 FNPP communities. Under this program, community safety plans are developed by communities based on individual safety needs. The program offers a basis for improved synergy through its support of community planning and the establishment of trusting working relationships in communities.

It is clear that alternative approaches need to consider community development principles such as community engagement and involvement; holistic and traditional FNs and Inuit practices; community responsibility and accountability; and embedded resources.

Recommendations:

That the Assistant Deputy Minister of Community Safety and Countering Crime Branch and the Assistant Deputy Minister, Emergency Management and Programs Branch of Public Safety Canada implement the following:

- Ensure that future policy and program objectives are communicated and incorporate elements that support a continuum of community capacity and responsibility, with alternative service delivery approaches.

- Develop criteria that assist in assessing community needs and capacity as they relate to public safety to guide discussions with communities and inform future program design and accessibility decisions.

- Develop an accountability mechanism to clarify the delineation and linkages between Provincial or Territorial Police Service Agreements and FNPP agreements where the RCMP is the service provider.

- Explore opportunities to increase flexibility in the funding model, including the duration of program funding and agreements, to better facilitate long-term planning for program recipients.

Management Response and Action Plan

Management accepts all recommendations and will implement an action plan.

1. Introduction

In the Government of Canada, evaluation is the systematic collection and analysis of evidence on the outcomes of programs to make judgments about their relevance and performance and to examine alternative ways to achieve the same results. To that end, The Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation requires that all ongoing programs of grants and contributions be evaluated every five years to support policy and program improvement, expenditure management, Cabinet decision making, and public reporting. Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act also requires contribution programs to be evaluated every five years. The last evaluation of the First Nations Policing Program (FNPP) was completed in 2010.

This report presents the results of the Public Safety Canada (PS) 2014-2015 Evaluation of the First Nations Policing Program (FNPP). The evaluation provides senior management at PS with an evidence-based, neutral assessment of the relevance and performance of the FNPP and identifies and assesses alternative program delivery approaches.

2. Profile

2.1 Background

The Government of Canada has had a longstanding interest in supporting policing efforts in First Nations (FNs) and Inuit communities where public safety challenges are often significant and complex. Three periods mark the history of policing in FNs and Inuit communities:

- In the 1960's, as a result of Supreme Court decisions that increased provincial jurisdiction over Aboriginal peoples both on- and off-reserve, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) began to withdraw from policing on-reserve in Quebec and Ontario. This withdrawal resulted in rural and often isolated Quebec and Ontario communities being the most chronically under-policed locations in Canada which contributed to a pattern of high rates of disorder, crime, and personal victimization.Note 10

- In the 1970's and 1980's, the federal government in partnership with provinces and territories (PTs) supported a number of different approaches to Aboriginal policing (i.e., Indian Special Constable Programs, Band Constable Program, Aboriginal Community Constable Program) and funded several self-administered police services (i.e., Manitoba's Dakota Ojibway Police Service and Quebec's James Bay Police Service). Inquiries and commissions across Canada sharply criticized how Aboriginal people were policed and typically called for major changes. The reports were unanimous in decrying the effectiveness of the policing of Aboriginal people in terms of sensitivity to cultural considerations, lack of community input, biased investigations, minimal crime prevention programming, and fostering alienation from the justice system by Aboriginal people.Note 11 In 1986, concerns about policing services in FNs communities led to the establishment of the Federal Task Force on Indian Policing, which conducted a national review of the on-reserve FNs policing policy.Note 12

- The 1990 Task Force report stated that FNs and Inuit communities did not have access to the same level and quality of policing services as did other communities in similar locations. In many cases, policing services were ineffective, inefficient and unresponsive to the needs of the FNs and Inuit communities they served. Some FNs and Inuit policing services were found to be unprofessional and lack appropriate accountability mechanisms and did not provide avenues for Aboriginal peoples to have a say in the type and level of policing services provided.Note 13 The crisis at Oka, Quebec, in 1990, underscored the need for professional, dedicated and community-responsive policing in FNs and Inuit communities, and was the catalyst for the creation of the FNPP.

In 1991, in response to these public safety challenges, the Cabinet approved the First Nations Policing Policy and the FNPP was established.

2.2 First Nations Policing Policy

The purpose of the First Nations Policing Policy is “to contribute to the improvement of social order, public security, and personal safety in FNs and Inuit communities, including the safety of women, children, and other vulnerable groups.” The policy objectives are:

- Strengthening Public Security and Personal Safety: to ensure that FNs and Inuit enjoy their right to personal security and public safety. This will be achieved through policing services that are responsive to the particular needs of FNs and Inuit communities and that meet applicable standards with respect to quality and level of service.

- Increasing Responsibility and Accountability: to support FNs and Inuit in acquiring the tools to become self-sufficient and self-governing through the establishment of structures for the management, administration and accountability of FNs and Inuit police services. Such structures will also ensure police independence from partisan and political influence.

- Building a New Partnership: to implement and administer the First Nations Policing Policy in a manner that promotes partnerships with FNs and Inuit communities based on trust, mutual respect, and participation in decision-making.Note 14

2.3 First Nations Policing Program

2.3.1 Program Description

The FNPP, a contribution program, is delivered through tripartite policing agreements among the federal government, provincial or territorial governments, and communities. The federal and provincial/territorial governments provide parallel financial contributions (52% federal and 48% provincial/territorial).

FNPP police officers are expected to provide day-to-day policing services to FNs and Inuit communities including enforcement, victim services, crime prevention, school visits, youth interactions, and inter-agency cooperation, and liaison with community.

There are two main types of agreements:

Self-administered (SA) Agreements:

These agreements are negotiated between Canada, the provincial or territorial governments and community, or group of communities. Such an agreement can be entered into when the Government of Canada wishes to provide a financial contribution for expenses incurred by a police service authorized and/or established by a provincial or territorial government and a FN or Inuit community (or communities), and where this community is (or these communities are) responsible for governing the police service either through an independent police governing authority (also known as a board, a police board, a designated board, or a police commission) or through the local band council or regional government or authority (as is the case in Québec). In this type of agreement, the police service provider is a FNs or Inuit police service.

Community Tripartite Agreements (CTAs):

These agreements are negotiated between Canada, the provinces or territories and the communities after the signing of a FNs Community Policing Service Framework Agreement. Under a CTA arrangement, the community (or communities) has a dedicated contingent of police officers from the provincial or territorial police force. Typically, CTAs are in place where the RCMP acts as the provincial/territorial police under a Provincial or Territorial Police Service Agreement (PPSA/TPSA) with the Government of Canada.Note 15 Community members are expected to work with their police services to help set policing priorities through community consultative groups that are representative of the communities.

A type of agreement which is not frequently used is the Municipal Quadripartite Agreements.Theseagreements sometimes referred to as QUADs, are negotiated between Canada, the province or territory, a community (or communities) and a municipal police service provider. Similar to a CTA agreement, the community has a contingent of municipal officers dedicated to the community.

In March 2013, the Government announced the renewal of the FNPP for a period of five years. The renewed Terms and Conditions (T&Cs) of the FNPP, which came into effect on April 1, 2014, emphasizes that policing funded by the program should be professionalNote 16, dedicatedNote 17 and responsiveNote 18 to FNs and Inuit communities.

2.3.2 Program Coverage

Program data from 2013-2014 shows there were 172 policing agreementsNote 19 resulting in 1,244.5 police officer positions. Of these agreements, 38 were SAs, 122 were CTAs and 3 were QUADs. The majority of SAs are in Ontario and Quebec. While most of these agreements are with FNs communities, five agreements are with Inuit communities. These agreements are in Quebec and Labrador covering 18 Inuit communities. FNPP is limited in the Territories. There is one CTA in Yukon. Policing in the Territories is provided by the RCMP through the TPSAs.

Table 1 illustrates PS's program data on FNPP coverage by regions and communities.

FNPP Population |

Community Population |

Coverage % |

FNPP Communities |

FNs and Inuit Communities |

Coverage % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

British Columbia and the North |

54,950 |

116,357 |

47% |

144 |

276 |

52% |

Prairies |

131,915 |

232,302 |

57% |

88 |

179 |

49% |

Ontario |

86,419 |

93,372 |

93% |

104 |

138 |

75% |

Quebec |

56,774 |

66,783 |

85% |

43 |

53 |

81% |

Atlantic |

17,159 |

25,978 |

66% |

18 |

39 |

46% |

Canada |

347,217 |

534,792 |

65% |

397 |

685Note 20 |

58% |

2.3.3 Resources

Table 2 illustrates the budget allocation for the FNPP. The FNPP has not received additional ongoing G&C funding since its ongoing budget peaked at $105 million in 2007-08. The funding shortfall that this created was risk-managed by the Department in 2008-09. In 2009-10, the program received a two-year temporary funding increase to maintain existing agreements ($10.7 million in 2009-10 and $16.5 million in 2010-11). Similarly, the program received in 2011-12 a two-year temporary funding increase to maintain existing agreements ($15 million in 2011-12 and $15 million in 2012-13). In 2013-14, the program received a temporary funding increase of $91.2 million over five years to maintain existing agreements. Table 2 illustrates the budget allocated during the past five years.

2010-11 |

2011-12 |

2012-13 |

2013-14 |

2014-15 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Salary |

4,301,775 |

4,336,300 |

4,303,778 |

4,353,879 |

4,164,046 |

O&M |

2,076,500 |

1,502,372 |

1,208,420 |

1,026,877 |

918,971 |

EBP |

860,355 |

867,260 |

860,756 |

870,776 |

832,809 |

Total Vote 1 |

7,238,630 |

6,705,932 |

6,372,954 |

6,251,532 |

5,915,826 |

Total Vote 5 (G&Cs) |

121,783,148 |

120,283,148 |

120,283,148 |

120,083,330Note 21 |

121,611,662 Note 22 |

Accommodations |

559,231 |

563,719 |

559,491 |

566,004 |

541,326 |

Total |

129,581,009 |

127,552,799 |

127,215,593 |

128,285,246 |

128,068,814 |

2.3.4 Logic Model

The logic model is a visual representation that links what the program is funded to do (activities) with what it produces (outputs) and what it intends to achieve (outcomes). Figure 1 presents the FNPP logic model.

Figure 1 – FNPP Logic Model

Image description

The FNPP logic model has 3 components. In the first component, Policy Formulation (Direction), there are two sets of activities which produce two sets of outputs. In the first set, there are 3 activities: develop and provide policy advice and policy positions; conduct research; and develop/disseminate knowledge. These activities lead to the following outputs: policy papers/recommendations; research studies; and knowledge-oriented resources. In the second set, there are 4 activities: consult/engage Federal, Provincial, Territorial stakeholders (Working Group, Assistant Deputy Minister Committees); consult/engage Aboriginal stakeholders; develop/disseminate knowledge; and manage external/public communications. These activities lead to the following outputs: partnerships with Federal, Provincial, Territorial and Aboriginal organizations; knowledge-oriented resources; and media lines/communique. The outputs from this component, Policy Formulation (direction) lead to immediate outcome A – Evidence-based policy advice; and B – Stakeholders are engaged. These two immediate outcomes lead to intermediate outcome D – Stakeholders and decision-makers have access to evidence-based information, analyses and advice.

In the second component, Program Development (Design), there are 2 activities: develop and update program directives and guidelines (example, Terms and Conditions); and develop measure and report on program performance on an ongoing basis. These activities lead to the following outputs: directives and guidelines; performance measurement strategy; and annual performance report.

In the third component, Program Implementation (Delivery), there are 3 activities: negotiate, develop, administer and monitor agreements; facilitate community capacity in the area of police governance; and stakeholder engagement with signatories, police service providers, and Aboriginal communities. These activities lead to the following outputs: frameworks and agreements; monitoring instruments (example, risk-based monitoring tool); community advisory bodies/governance boards; and partnerships.

The second and third component outputs lead to immediate outcome C – First Nations/Inuit communities have access to FNPP. This immediate outcome leads to intermediate outcome E – Police services in FNPP-funded communities are professional, dedicated and responsive.

Intermediate outcomes from all three components lead to long term outcome F – Crime are attenuated and community safety is strengthened in FNPP-funded communities.

Outcomes A to E are more directly attributable to federal responsibilities whereas the final outcome F is not directly attributable.

2.4 Other Public Safety Community Safety Initiatives

PS administers two other programs that contribute to similar intermediate and ultimate outcomes. The results of these other two programs influence the achievement of FNPP results. Not all communities are participants in all three programs. Summaries of these programs are presented here in order to provide readers with a more complete picture of PS activities in support of the safety and security of Aboriginal communities.

2.4.1. National Crime Prevention Strategy

The National Crime Prevention Strategy is an important component of the Government of Canada's agenda to tackle crime and create safer neighborhoods and communities. Established in 1998, the Strategy is the federal government's main policy framework for the implementation of crime prevention policies and interventions in Canada.

The Strategy is based on the premise that well-designed interventions can have a positive influence on behaviors, and that crimes can be reduced or prevented by addressing risk factors that can lead to offending. Successful interventions have also been shown to reduce victimization, as well as the social and economic costs that result from criminal activities, including the costs related to the criminal justice system.

Through the Strategy, PS provides time-limited funding for the development, implementation and evaluation of evidence-based interventions, as well as for the development and dissemination of practical knowledge, with a view to fostering the development and adoption of effective prevention practices in Canadian communities.

Through Budget 2008, the Strategy was refocused with total ongoing funding of $63 million per year. Since then, its G&Cs funding has been reduced to $40.9 million, ongoing. Currently, the Strategy focuses on the following priority groups: children (6-11), youth (12-17) and young adults (18-24) who present multiple risk factors related to offending behaviors; Indigenous people and Northern communities; and former offenders who are no longer under correctional supervision.

According to the 2012-2013 evaluation of PS's crime prevention programs, 94 projects were funded in 67 locations across Canada representing an investment of about $31 million. Of the 94 projects, 43 focused on Aboriginal youth. These projects reached an estimated 23,000 at-risk individuals such as members of youth gangs, Aboriginal youth on-reserve and in urban centers and high-risk repeat offenders across Canada.

Overall, the evaluation reported that these programs, including those involving the Aboriginal youth, had been successful in building community capacity in terms of positive changes in knowledge and awareness, attitudes and skills; positive changes in risk and protective factors and/or anti-social behavior; and changes in offending behavior and/or gang membership.

2.4.2. Aboriginal Community Safety Development Program

This program funds the development of tailored approaches to community safety that is responsive to the concerns, priorities and unique circumstances of Aboriginal communities. The program provides funding for knowledge building and sharing, capacity building, implementation readiness and implementation. The objectives of the program are to enhance or improve communities' abilities to support the development and/or implementation of community safety plans. There are two key elements that support these objectives:

- The development and implementation of effective models (supporting community-based projects designed to explore and implement holistic, Aboriginal models of community safety).

- Support communities to enhance willingness, capacity and readiness to implement models (developing community capacity through knowledge building, knowledge sharing and capacity building).Note 23

A 2014 evaluation showed that, by September 2012, the program had delivered workshops in 25 communities and that PS had received nine safety plans. Other communities were still working on earlier stages of readiness.

3. About the Evaluation

3.1 Objective

The objective of the evaluation is to support program renewal by identifying and assessing alternative program delivery approaches, and to provide the Deputy Minister of PS with an evidence-based, neutral assessment of the relevance and performance of the FNPP.

3.2 Scope

The evaluation assessed the relevance and performance of the FNPP.Note 24 In particular, it reviewed earlier studies that focused on administrative aspects of the program. It also gathered new data to examine the FNPP's policy response, funding model, and alternative delivery approaches as directed by the PS Departmental Evaluation Committee in November 2014.

3.3 Methodology

This evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board of Canada Policy on Evaluation, the Standard on Evaluation for the Government of Canada, the PS Evaluation Policy, the Policy on Transfer Payments, and the Financial Administration Act.

The evaluation approach and methodology and level of effort were determined in light of the following factors:

- For the most part, the FNPP has remained relatively stable. The FNPP policy has not changed since 1996. There has been relatively no change in funding or number of overall agreements since 2007.

- This evaluation built on the 2010 PS evaluation as well as other recent reports such as the May 2014 Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) performance audit.

- The PS Program, Performance and Analysis team of the Community Safety Programs Division has been developing performance measures and collecting data relating to the FNPP. The evaluation team leveraged this work, incorporating the available performance data into the evaluation.

3.3.1 Evaluation Questions

Subsequent to consultations with PS's Departmental Evaluation Committee, the following questions were identified to be addressed in the evaluation.

Relevance

- How does the FNPP contribute to safe and secure communities? Where are the gaps?

- Which levels of government are best positioned to deliver the FNPP?

- Which federal departments or agencies are best positioned to oversee a response to the need for safe and secure First Nation and Inuit communities?

Performance

- Is the FNPP in its current format addressing the need for safe and secure First Nation and Inuit communities?

- Is the current funding model of contribution agreements a viable model for the development of safe and secure First Nation and Inuit communities?

- In what way could the FNPP be refocused to maximize the value-added of the government investments in responding to the need for safe and secure First Nation and Inuit communities?

- In what way would the stakeholders (e.g., federal, provincial/territorial governments and the First Nations, etc.) work together to consolidate the FNPP gains made so far and move to place FNPP on much firmer financial, operational, and legal grounds?

3.3.2 Lines of Evidence

Document and Literature Review

The evaluation reviewed many documents for the evaluation including previous evaluations and audit reports, relevant legislation, reports on plans and priorities, performance reports, speeches from the throne, budget documents and other relevant material provided by the FNPP policy and program authorities.

For the literature review, a comprehensive web-based search of public documents was conducted. Annex A lists the documents that were reviewed.

Interviews

As shown in Table 3, 64 interviews were conducted using interview guides tailored to each stakeholder group.

Interview Group |

Number of Interviews |

|---|---|

PS policy and program representatives (headquarters and regions) |

11 |

Provincial/territorial representatives |

12 |

First Nations Associations |

2 |

Other government departments and agencies |

7 |

First Nations and Inuit communities |

20 |

Police officers |

12 |

TOTAL |

64 |

Interviews were held with regional, program and policy managers from headquarters for FNPP and other PS related programs (i.e. Community Safety and Crime Prevention), provincial and territorial members of the Federal/Provincial/Territorial FNPP Working Group and national Aboriginal organizations including the Assembly of First Nations and the First Nations Chiefs of Police Association. Representatives from the following departments and agencies were also interviewed: Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, Justice Canada, Privy Council Office and the RCMP.

In order to limit the level of effort, the evaluation team interviewed community representatives and police officers chosen from a sample of agreements from the following locations: Atlantic Canada, Quebec, Saskatchewan and British Columbia. Interviews were not conducted in Ontario, Manitoba, and Alberta as opinions from FNs communities in these provinces were sought by the OAG for the 2014 Spring Report.Note 25 The final interviewee sample was chosen with the guidance of the regional managers based on coverage of the types of agreements the guidance of the regional managers based on coverage of the types of agreements (CTAs, SAs and QUADs), and geographic location (urban, rural, and isolated). The resulting distribution of interviewees with community representatives and police officers was as follows:

First Nations and Inuit Communities |

Police officers |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

In-person |

Telephone |

In-person |

Telephone |

|

Atlantic |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

Quebec |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

Saskatchewan |

9 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

British Columbia |

3 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

TOTAL |

16 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

Focus Groups

Three focus groups were conducted including, 1) academia, 2) senior and middle management of PS, and 3) other federal government departments. Participantswere asked to respond to the evaluation questions from their professional perspectives as well as to build on comments from others.

Program Performance Information

Information pertaining to the administration of the program (e.g. financial information, agreement risk, community names, and number of officers) and the attributes of the communities (e.g. population and geographical location) were retrieved by program staff from the department's information management system.

Information used to assess the implementation and impact of the program was obtained from the following program documents:

- 2013-14 FNPP Annual Program Performance Report (March 2015).

- 2014 Questionnaire of CTA Communities (RCMP Non-Financial Reporting Tool).

- 2014 FNPP Service Provider Questionnaire.

In addition, information on current and past pilot projects was used to assess alternative delivery approaches.

3.4 Limitations

The following section describes data limitations.

The 2014 questionnaire of CTA communities was based on responses from 83 out of 120 agreements. The results can provide insight but cannot be generalized to all communities. The questionnaire did not include communities with SAs.

In addition, the 2014 FNPP police service providers questionnaire, administered to both SAs and CTAs, was based on the response from 393 out of 1244 police officer positions. The results can provide insight but cannot be generalized to all service providers. The evaluation team triangulated performance data with other lines of evidence to confirm findings.

For past pilot projects on alternative delivery approaches an evaluation was not always conducted; thus, information on these pilots is limited. Some pilot projects are underway; therefore, review is not yet available. The evaluators conducted interviews and reviewed available documents on both past and current pilot projects to obtain information on the pilot projects.

Community interviews are not representative of the national FNs and Inuit population. The interview selection was based on availability and willingness of communities to participate, and also on the geographical location of communities (proximity to cities). In order to mitigate the geographic factor, a limited number of interviews were conducted with individuals in isolated communities by telephone. However, only one interview was conducted with individuals from an Inuit community. The evaluation relied on the document review to mitigate these limitations.

3.5 Protocols

During the data collection for the evaluation, PS program and policy representatives assisted in the identification of key stakeholders and provided documentation and data. During the reporting phase, the evaluation team met with policy and program management to review the findings and conclusions.

This report was submitted to policy and program managers and to the responsible Assistant Deputy Ministers for review and acceptance. PS program and policy representatives prepared a Management Response and Action Plan in response to the evaluation recommendations. These documents were presented to the PS Departmental Evaluation Committee for consideration and for final approval by the Deputy Minister of PS.

4. Findings

4.1 Relevance

4.1.1 Continued Need

Research has identified a connection between certain demographic and social factors and an elevated risk of offending and/or victimization. These factors include living in a single-parent family situation, living common-law, being unemployed and abusing alcohol. All of these risk factors are apparent in the demographic and social conditions of the Aboriginal population in Canada.Note 26 For example, Statistics Canada data from 2011 demonstrated that Aboriginals had lower educational achievement and were economically disadvantaged; about one-third of Aboriginal children lived in a lone-parent family compared with about one in five non-Aboriginal children. Aboriginals are far more likely than other Canadians to be victims of violence.Note 27

Performance reports indicate that, from 2004 to 2013, the crime rate in FNPP communities declined as it did in the rest of Canada.

Type of Crime |

FNPP Communities (n=44) |

Rest of Canada (n=728) |

|---|---|---|

Crime (Excluding Traffic) |

17% |

33% |

Violent Crime |

20% |

21% |

Assaults |

20% |

19% |

Sexual Assaults |

12% |

15% |

Despite the ten-year reduction in FNPP communities, crime and victimization in many FNs and Inuit communities remains higher than in the rest of Canada. As shown in Table 6, in 2013, incidents of crime on-reserve (excluding traffic) remain almost four times higher than in the rest of Canada, and incidents of violent crime were just over six times higher. Incidents of assault and sexual assault were about seven times higher.

Type of Crime |

FNPP Communities (n=44) |

Rest of Canada (n=728) |

|---|---|---|

Crime (Excluding Traffic) |

4848 |

19,276 |

Violent Crime |

6,106 |

996 |

Assaults |

3,724 |

523 |

Sexual Assaults |

366 |

54 |

Theliterature suggests that crime rates in FNs and Inuit communities remain high due to social problems. According to the document review, interviews and the 2014 questionnaire of CTA communities, alcohol abuse, drug use and domestic violence are common social issues in FNs and Inuit communities. Police officers have consistently and increasingly addressed “unsolvable social problems” that tax policing resources.Note 28 The extent to which mental health and associated social disorder issues burden modern police work has been noted by subject matter experts.Note 29 Interviewees and focus group participants pointed out that policing is not the sole answer to reducing crime in FNs and Inuit communities.

Despite continuing high crime rates and ongoing social problems, police officers and community members reported that the communities where they live and work are safe and more secure. In the 2014 FNPP Service Provider Questionnaire, 41% of the respondents indicated that the communities they serve are safe, while 43% indicated communities were somewhat safe and 16% that they were not safe. The 2014 questionnaire of CTA communities revealed that 78% of the communities that responded felt that their community is safe, while 22% said it was not. Data is not currently available for communities with SAs.

Interviews support these findings. First Nations Associations, communities and service providers generally feel that the FNPP is contributing to safe and secure communities and has made a difference.

4.1.2 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

There is no specific constitutional or legislative requirement for the federal government to provide policing services to FNs and Inuit communities. The decision to provide funding for policing is a matter of policy.Note 30

The Program theory was that FNs and Inuit communities should be involved in the negotiation of agreements and engaged in setting policing priorities through community consultative groups or police management boards. Focus groups with academics and other government departments commented on the need to have all stakeholders involved in policing FNs and Inuit communities. Emphasis was placed on the need for the federal government to support FNs and Inuit communities in acquiring the tools to support increased responsibility and accountability.

While policing is regulated concurrently by Parliament and provincial legislatures, policing is considered to be primarily the responsibility of the provinces. Provincial authority for policing is found under Section 92(14) of The Constitution Act, which outlines provincial jurisdiction for the administration of justice. This section gives provincial legislatures the authority to enact laws establishing police forces and regulating the appointment, supervision and discipline of members of these forces. These provincial policing laws of general application apply to FNs reserves.

As stated in the 2010 FNPP evaluation, the majority of provincial governments and other federal departments/agencies interviewed suggested that coordination should be led at the national level but policing should be planned and managed primarily at the provincial level with participation from FNs and Inuit communities. The view of provincial respondents was that there is a very important role for the federal government to play in coordinating policing services with those of health, social services and other related functions. The provinces should be involved in the day-to-day administration of the agreements as they are the ones responsible for general policing and policing standards.Note 31

Focus group participants and interviewees commented that PS is the federal department best suited to coordinate the program due to its role in keeping communities safe and secure. Promoting safer communities maximizes the benefits of federal investments in areas such as health, education social and economic development services. A community that is safe provides the foundation for its members to become resilient and thus anticipate, mitigate and manage threats and hazards that may emerge.Note 32

4.2 Performance - Effectiveness

4.2.1 Access to Police Services

The FNPP was meant to ensure FNs and Inuit communities enjoy their rights to personal security and public safety through access to policing services that meet their needs. In terms of providing this access, program and policy representatives indicated that the original policy goal in 1991 was to cover 100% of FNs and Inuit communities. Today across Canada, there are 688 communities (635 FNs communities and 53 Inuit communities) with a total population of 534,792Note 33. In 2013-14 the FNPP provided funding for policing services in 397 out of 688 FNs and Inuit communities (58%) representing a total population of 347,217 people (65%).

The 2014 OAG audit found that the program was not accessible to all FNs and Inuit communities. In 2007, ongoing funding was frozen at $105 million making it difficult for to expand access to the program. Interviews and document review indicate that reallocation of resources would be challenging because funding decisions are based on the historical footprint and on the availability of funding. Business cases were presented to support the initial allocation of funds, but there was no systematic approach for the allocations. Program and policy staff, along with PT representatives commented that it is now difficult to shift resources from FNPP-funded communities to non-FNPP funded communities.

Focus group discussions raised the idea of making funding decisions based on the Community Well-Being Index,Note 34 crime rates or other data. Both interviews and focus groups raised the challenge of having an existing funding footprint and being unable to reduce resources in one community to reallocate to another, given the impact on existing police services and the ongoing need for policing in these communities.

Provincial/Territorial and community representative interviewees noted a desire to expand the program to more rural and remote and northern communities where factors affecting criminalization and victimization rates are more pronounced. Currently 84 rural and remoteNote 35 communities are funded under FNPP.

4.2.2 Increasing Community Responsibility and Partnership

Evidence shows that community engagement and responsibility are essential for successful program administration, design and delivery. FNs and Inuit programs communities need to be engaged, own the program, and set the pace. These notions are stated in the overarching policy objectives of the FNPP. These objectives focus on providing policing services that are responsive to the needs of communities and on providing support for tools to increase responsibility and accountability. PS was to implement and administer the FNPP in a manner that promotes partnerships based on trust, mutual respect, and participation in decision-making. In general, the Program has not sufficiently engaged and supported communities so as to build partnerships and capacity that would enable achievement of outcomes.

Delivery has focused on the T&C objectives – that policing should be responsive, professional and dedicated. Throughout the interactions with program, policy officers and stakeholders, it became apparent that few were aware of the overarching policy objectives. Most were aware of the T&C objectives related to professionalism, dedication and responsiveness of police services. Few PS employees knew the overarching policy objectives meant to develop community responsibility and build new partnerships.

This focus was further complicated by the fact that some stakeholders added their own interpretation of objectives. Service providers and some PTs spoke about the FNPP as an “enhancement” to police services provided under PPSAs. They described “enhanced services” to be such things as victim services, crime prevention, school visits, liaison with community, youth interactions, inter-agency cooperation and other community-based activities. Under the FNPP, these activities are considered to be part of policing. The notion of “enhanced policing” does not align with policy objectives, T&C objectives or PS policy or program management instruments.

The importance of ensuring the increased responsibility of communities in program administration, design and delivery to achieve program success was illustrated in the literature review, interviews and focus groups. The literature shows that programs are more successful when communities are engaged, own the program and set the pace.

Several studies examined why mainstream programs often fail:

- They are not designed to consider needs of Aboriginals.

- They do not take into account language, culture, traditions, and current life situations.

- They do employ non-Aboriginals.Note 36

The document review showed that negotiation with communities when establishing or renewing agreements has been limited. The 2010 FNPP Comprehensive Review and the 2010 FNPP Evaluation both commented on the need for communities to be involved in the negotiation process from the beginning. The documents also indicated that for communities to have an appropriate role in working with their police service there must be continued emphasis on building tripartite relationships among the federal government, the province and the community. In addition to these key relationships, there is a need for communication, interaction, collaboration, and engagement between communities and police officers.Note 37 The findings are supported by the 2014 audit of the FNPP by the OAG that found that communities did not always have meaningful input when entering into new policing agreements or renewing existing agreements.

Interviews and focus groups supported the findings of the document review. Communities that were interviewed indicated that they would like “more say” before signing or renewing agreements. They commented that not all parties are on equal footing as final agreements were presented to communities for their approval with little or no prior engagement or consultation. Communities indicated that they need to be more involved in the negotiation process from the beginning.

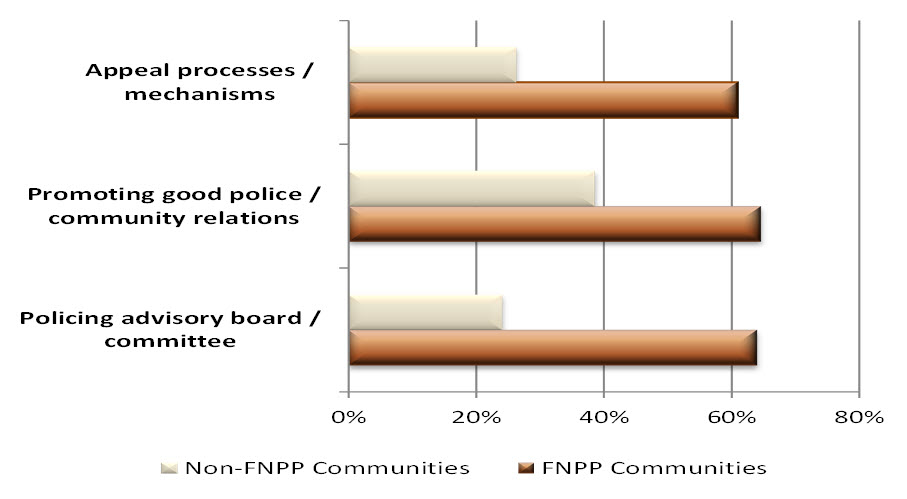

In addition to being involved in establishing and renewing policing agreements, it is also important for communities to have structures to advise their police services on community policing priorities and hold police services accountable for their performance. Figure 2 illustrates the success of the FNPP program against unfunded communities. Roughly 60% of FNPP communities have governing structures in place; this is in contrast with the less than 40% of non-FNPP communities that do not. In particular, communities accessing the FNPP were 2.7 times more likely to have a community policing advisory board. They were 1.7 times more likely to promote good police/community relations. They were also 2.3 times more likely to have appeals processes/mechanisms in place to deal with community complaints regarding police activity. Despite this success, it is noted that the program's T&Cs require all CTAs and SAs to have a mechanism to engage communities to participate in setting policing priorities. As such, there is still room for improvement as about 40% of FNPP communities do not have these police management boards or community consultative groups.

Figure 2 –2010 First Nations Information Governance Centre's Regional Health SurveyNote 38

Image description

The graph shows the percentage of non-FNPP and FNPP communities that have 3 types of governing structures in place. For non-FNPP communities, 26% have appeal processes/mechanisms; 39% promotes good police/community relations; and 24% have a policing advisory board/committee. For FNPP communities, 61% have appeal processes/mechanisms; 65% promotes good police/community relations; and 64% have a policing advisory board/committee.

The 2010 PS Evaluation of the FNPP identified governing of police service providers as a predominant theme and recommended that communities should be supported to strengthen the ability of their community consultative groups and police management boards to oversee the performance of their police services against the objectives of the FNPP. In addition, the 2010 comprehensive review highlighted issues relating to how governing and advisory bodies function and how and why some are not meeting the requirements stipulated in their FNPP agreements. The reasons identified included a lack of funding for members; lack of training for new or existing members; disinterest among community volunteers in participating on advisory bodies; language barriers; and a lack of capacity at the community level to understand the requirements for governing.

Interviews conducted as part of this evaluation note similar results. Of the 18 communities interviewed requiring community consultative groups (or police management boards),Note 39 12 had them and six did not. Communities indicated that while they were working more collaboratively with police, in many cases priorities were identified by the police and not the communities.

Communities identified the following challenges in communicating community safety priorities:

- Poor communication.

- Lack of human and financial capacity (i.e. insufficient volunteers, no funding for training).

- Lack of support from the leadership and community.

- Frequent changes in community leadership and police officers.

4.2.3 Responsiveness

Program documents show that police services in FNs and Inuit communities are expected to be responsive to the cultural specificities of the communities they serve.

The issue of cultural responsiveness of police services is not a recent one. The 2010 comprehensive review noted that strengthening community governing of police service providers is an integral component of making service providers accountable, responsive, and culturally appropriate. Communities should be encouraged to engage in regular dialogue with local police services to provide them with information about their culture, local community dynamics, and indigenous approaches to justice and problem solving. The 2010 Evaluation noted that cultural appropriateness, responsiveness and accountability to communities were areas that required attention. It also noted that improvement can be made when community governing of police service providers is strengthened and when police services adopt approaches that include greater involvement and engagement of the communities.

Community members perceive that responsiveness of police officers has improved since 2010 in both SA and CTA communities. Interviewees from communities that have SAs in place emphasized the importance of having their own police services. They commented that without their own police services, officers would not know or understand the community. They noted that the historical relationship with provincial police is one of mistrust and fear. Police officers who are culturally aware help to build relationships with community members and make links with other services in the community that would not be possible with provincial police officers. Interviews and focus groups noted that a key advantage of a FNs police service under a SA is that the police are embedded in the community and, as they are from the community, they are responsive to the cultural needs of the community they serve. In the 2014 questionnaire of CTA communities, 86% of communities that responded indicated that police services are being delivered in a manner that is respectful of their culture, while 14% indicated they were not. Despite this result, CTA community interviewees had some mixed views about the cultural responsiveness of police officers. Interviewees noted the following challenges to cultural responsiveness:

- Getting the right people and having them properly trained is crucial.

- Overworked officers cannot meet the needs.

- Importance of engaging the communities and changing attitudes towards the police.

- Transient nature of leadership at all levels often means starting over.

4.2.4 Professionalism

One of the FNPP priorities is to provide professional police services. This means that police officers are expected to adhere to provincial or territorial standards, as well as policies or procedures developed by the police service and police governing body, and to have completed a recruit training program at a police academy recognized by the province or territory.

Police officers, like those in other occupational groups, must abide by provincial standards and regulations and must meet specific educational and/or training requirements.Note 40 A 2014 questionnaire conducted by the program as well as interviews conducted for this evaluation noted that police are professional and that they are all trained to the provincial standard.

A discrepancy noted by SA police officers is in the provision of continuous training. CTA officers have access to RCMP training while SA officers have limited resources to support ongoing training. Police officers working under SAs also noted the limited resources available for job-related tools (i.e., vehicles, digital prints, etc.) which affect their ability to carry out their duties.Note 41

4.2.5 Dedication

FNPP-funded police officers are expected to dedicate their on-duty time and efforts only to providing policing services to the communities they serve. The 2014 FNPP service provider questionnaire showed differences in dedication of police officers' time by type of agreements. A high percentage (85%) of the officers funded under SAs who responded indicated that their time is dedicated to the community. This compared to 53% of officers funded under a CTA. In these CTA communities, the intent of having dedicated FNPP officers has been eroded since the FNPP is supplementing PPSA activities. Police are spending their time on provincial duties rather than on FNPP activities. With this lower level of dedication, opportunities for community engagement and responsiveness are lost.

Police services funded under a SA were seen by interviewees to be dedicated to their communities to a greater degree than police working under CTAs. Communities that have SAs reported that their police are always present as the officers work and often live in the communities. In contrast, communities with a CTA had mixed views on the dedication of police officers. Some interviewees commented that CTA police were present and if not, they were still doing work for the community, whereas others did not feel that police were in the community frequently enough.

Interviewees noted the following challenges with dedication of officers under CTAs and SAs:

- Blurred lines between the PPSAs and the CTAs.

- Not enough officers or officers on leave too frequently.

- Reactive policing.

- Staffing difficulties in isolated communities.

- No police detachments in some communities.

Focus groups spoke about the need to have police officers embedded in the communities so that 100% of their time would be spent there and they would be familiar with the cultural components of the communities they serve and have relationships with community members.

Interviewees noted that there are advantages to having a dedicated contingent of officers serving their communities under a CTA rather than receiving policing services from the provincial police. These advantages included linkages between the communities and the police, the establishment of meaningful relationships with the community, and increased willingness on the part of community members to report crime.

4.3 Performance – Efficiency and Economy

4.3.1 Funding Model for First Nations and Inuit Police Service

The evaluation examined the viability of the current contribution agreement approach to deliver FNPP-funded policing services.

Based on information from all lines of evidence, contribution agreements are not an ideal funding model that lends itself to the delivery of a service like policing that requires long-term planning. The 2010 evaluation noted that a major and consistent criticism of contribution agreements is the requirement for frequent renewals. The renewal process was seen as being inefficient, unnecessarily expensive and detracting attention from issues that are more central to the effectiveness of policing such of adopting more holistic and collaborative processes. Interviewees suggested the minimum timeframe for renewal should be five years and most argued for at least ten years. Some noted that agreements could be 20 years like the PPSAs. It was suggested that it would be preferable for FNPP agreements and PPSAs to have the same duration.

In a 2011 report, the OAG found several challenges that were generally associated with the use of contribution agreements to fund the delivery of services on FNs reserves:

- Most contribution agreements must be renewed yearly, and funds may not be available until several months into the funding period. As a consequence communities may have to reallocate funds from elsewhere and funding uncertainty precludes long-term planning.

- The use of contribution agreements between the federal government and FNs communities may also inhibit appropriate accountability. While the services to be provided or actions to be taken are stated, contribution agreements do not always focus sufficiently on service standards or results to be achieved.

- Contribution agreements involve a significant reporting burden which is particularly problematic for small FNs with limited administrative capacity.Note 42

Interviewees echoed these observations stating that there is a need for long-term planning for a service such as policing. They also noted that accountability for results is not clear and that there is a heavy bureaucratic burden associated with the renewal process. Focus group participants agreed that the current short-term and fixed funding for contribution agreements are not working well as it does not allow for long-term planning.

In addition, prior to 2013, the T&Cs set out a maximum spending limit for capital expenditures of $2.1 million per year. Temporary authority to spend beyond this limit on was obtained in 2009-2010 and 2010-2011, pursuant to temporary funds allocated in Budget 2009 for capital expenditures. Since 2014, there has been no maximum spending limit in the T&Cs with respect to capital infrastructure. Nevertheless, the program is unable to systematically address infrastructure needs due to the general funding limitations and the lack of ongoing or dedicated funding for capital expenditures. In comparison, it should be noted that infrastructure costs are accommodated in the PPSAs. Infrastructure has been an issue for years and remains an ongoing challenge. Infrastructure costs were not included in the original FNPP budget because it was the position of PS throughout the 1990s that these costs would be covered by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada.Note 43 Although rent is an eligible expense under the FNPP that is used in many instances to “reimburse” a community's investment in policing infrastructure, communities often do not have the capacity or resources to provide offices that meet required security standards. Interviewees noted that this is particularly challenging in isolated communities where finding proper space is complicated by community housing shortages. According to the document review, facilities and buildings, communication systems, housing for officers and maintenance of police equipment were among the infrastructure issues that FNs and Inuit communities across Canada face.Note 44

In 2014, the OAG report illustrated that PS does not have reasonable assurance that policing facilities in FNs and Inuit communities are adequate. The audit found that some FNs and provinces continue to raise concerns regarding the state of policing facilities.Note 45

4.3.2 Horizontal Approach

To examine how the program could be refocused to maximize the return on government investments, the evaluation looked at how different federal departments were collaborating on FNs and Inuit issues as well as how the Federal Government was working with provinces and territories and other partners such as national Aboriginal organizations.

Interviews with provinces and territories and communities found that linkages and collaboration were occurring at the community level. Both focus groups and interviews identified the need for the Federal Government to stop working in silos and address FNs and Inuit issues from a holistic approach by making strategic investments.

All lines of evidence noted the need for a horizontal approach that involved all partners at the federal, provincial and community levels. Other government agencies with specific mandates to deal with other sectors such as health, employment and training, justice, and natural resources and northern development should also be involved.Note 46

A recent report of an expert panel on the future of Canadian policing approaches models has recognized that safety and security are influenced by a wide range of institutions and organizations both inside and outside of the government. The justice system, the education system, and correctional system, for example, have all been shown to be able to reduce and prevent crime. With respect to policing, a recent report goes even beyond the notion of whole-of-government by emphasizing that the production of safety and security is a whole-of-society affair involving multiple and many mandates.Note 47

The focus groups supported by the literature review noted that collaboration with other jurisdictions and service providers can facilitate integration and consolidation of policing services. Benefits of the integration of policing services include reduction of duplication and overlap which in turn would yield efficiencies through economy of scale and the use of shared equipment and technology amongst others.Note 48

In particular, focus groups identified that in order to maximize the value of the government's investment, the program should engage stakeholders, particularly key members of the FNs and Inuit communities, such as youth and the elders to gather their input and obtain their involvement.

4.3.3 Alternatives

Almost two decades after the implementation of the FNPP there has been comparatively little academic research undertaken on the program. Few best practices associated with Aboriginal policing have been identified. The most effective service approaches have not been determinedNote 49. However, the literature review reveals that any approach can only be successful if communities become full partners and take ownership of the solution.

As part of the 2010 FNPP evaluation, the evaluators examined the literature review commissioned by the Ipperwash Inquiry. The inquiry found consensusNote 50 in three areas:

- There is potential for community policing approaches to reduce crime and to improve relationships between police and the persons they are to serve.

- In relation to governing approaches, Aboriginal persons must be given greater control over police services and in turn, must be more accountable for results.

- In relation to recruitment, training, and retention of police officers, key dimensions of a successful approach were noted. These include: screening for racism; recruitment of more Aboriginal persons to police service; employee and family assistance programs; and cross-cultural training that utilizes Aboriginal officers.

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples proposed principles to guide reforms in health and healing services that could be applied to other Aboriginal programs. These principles indicate that solutions should be:

- Based on holistic concepts of health and well-being firmly rooted in Aboriginal traditions.

- Controlled by Aboriginal people themselves.

- Provide services that are equitable compared to those available for other Canadians and that are founded on a respect for cultural diversity.Note 51

According to Hylton (2005), successful programs grow from community initiative and are nurtured by community development principles. Many studies and enquiries on the essential principles of community development in FNs and Inuit communities have included the following three themes for consideration when designing programming:

- Holistic approaches

- Community accountability for safety and security.

- Resources embedded in the community.Note 52

Tiered Policing

This approach broadens the categories and types of persons employed by a police service. Employees can range from full sworn police officers to civilian volunteers. They perform various police functions with a view to reducing policing costs as not all tasks need to be completed by a sworn police officer.

Using a tiered policing approach, the File Hills Constable Pilot Project was implemented in Saskatchewan in an FNPP community within an existing SA agreement. The objectives of the pilot project was to hire, equip, and train five Special Constables to provide support to policing functions such as community outreach and public information presentations. The constables implement and maintain a level of policing that was culturally sensitive and that would enhance public safety within the community. It was found that hiring police officers from the community who report to the Chief of Police helped with cultural sensitivity. It is noted that in order for this approach to succeed, there is a need for a high functioning community governance and strong community-based support.

Multi-agency Approach to Social Issues

This is not a policing approach per se. It is one part of a Community Safety model designed to improve a much broader set of social outcomes, including reducing crime, violence and victimization. Pilot projects using this approach have been implemented in several FNPP communities under the HUB and Social Navigator models.

The HUB is an evidence-based collaborative problem solving approach that draws on the combined expertise of relevant community agencies to address complex human and social problems before they become policing problems. This approach has been implemented as a pilot project in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. The HUB approach has been found to enhance collaboration and communication between police and other community agencies and assist in mitigating acutely elevated risk of harm or victimizationNote 53.

The Social Navigator was modelled from the Prince Albert HUB and is being implemented by the United Chiefs and Councils of Mnidoo Mnising Anishnaabe Police force in Ontario. Here the Social Navigator‘s job is to refer people who have had repeated encounters with the police and have been identified as at-risk individuals to the appropriate service provider for the needs of each individual in order to get to the root causes of the deviance and to keep that individual out of the criminal justice system. The social navigator's role is to maintain cultural practices and understandings while addressing the full spectrum of crime reduction. The social navigator pilot was underway at the time of the evaluation.

Community Safety Plans (Aboriginal Community Safety Development Program)

As of December 2015, PS had received community safety plans from 16 FNPP communities. The development of these plans was funded under the Aboriginal Community Safety Development program. The community safety plans are developed by the communities themselves based on the individual safety needs of the community. This community-led approach is effective in improving the health and safety in Aboriginal communities, in initiating community engagement and community mobilization. As such, the Aboriginal Community Safety Development Program offers a basis for improved synergy through its support of community planning and the establishment of trusting working relationships in communities. At its best, the Program offers a platform to transform the way departments and agencies operate in addressing complex, interdependent issues such as those experienced in many Aboriginal communities.

In discussing alternative approaches, interviewees identified similar important considerations including community engagement and involvement; integration of traditional methods; the need for more FNs and Inuit officers; innovation in finding new policing approaches; customization of approaches to community needs; and the need to broaden the safety program to include more crime prevention activities.

5. Conclusions

Relevance

A program that addresses safety and security in FNs and Inuit communities remains relevant and necessary. From 2004 to 2013, the overall volume of crime in FNPP communities declined as it did in the rest of Canada. However, the incidents of crime on-reserve still remained almost four times higher, and incidents of violent crime were about six times higher than the rest of Canada. Risk factors of offending and victimization are higher among the Aboriginal population. In this broader social context, policing is not the sole answer to reducing crime in FNs and Inuit communities.

In terms of roles and responsibilities, all levels of government and communities themselves have a role to play in the FNPP. The Government of Canada has a role in coordinating police services in FNs and Inuit communities. However, it is important that communities are engaged in order to participate in setting policing priorities and negotiating agreements. Policing should be planned and managed primarily at the provincial/territorial level as it is this level of government that is responsible for general policing and policing standards.

Due to its role in keeping communities safe and secure, PS is the federal department best suited to play a coordination role for the FNPP. It is also well suited to maintain linkages to other federal investments in FNs and Inuit communities in the area of health, education, social services and economic development.

Performance

Evidence shows that community responsibility is essential for successful program administration, design and delivery. FNs and Inuit communities need to be engaged, own the program and set the pace. These notions are stated in the overarching policy objectives of the FNPP. The evaluation found that the Program has not sufficiently engaged communities so as to increase community responsibility.

Although the FNPP has made a difference in funded communities, gaps persist as the program is not accessible to all communities. The evaluation acknowledges that funding has been frozen since 2007, leaving little opportunity to expand the program into remaining communities. There is a lack of community-based needs information, and historically, there was no systematic approach for the funding allocations. Given these factors, the evaluation team could not determine if the existing funding envelope could be used to expand the program into remaining communities to address the gap.

The evaluation notes that most stakeholders have focused on the achievement of objectives included in the program's T&C objectives. Few stakeholders were aware of the overarching policy objectives.

The evaluation found that contribution agreements are not the ideal delivery mechanism for FNPP. This was also noted in the 2010 evaluation and the 2014 OAG report. Contribution agreements require frequent renewals and there is a heavy administrative burden associated with each renewal. This factor and funding uncertainty precludes communities and police services from conducting long-term forward planning.

In terms of alternative delivery approaches, few best practices associated with Aboriginal policing have been identified. However, literature review reveals that an approach can only be successful if communities become full partners and take ownership of the solution. Through implementation of several pilot projects, PS has explored innovative approaches to address the increasing cost of policing and to offer better community engagement. These approaches include the principles found in recent studies of economics of policing and integrate a more holistic, community-based solution into existing programming.