2013-2014 Evaluation of the National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet

Table of contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Profile

- 3. About The Evaluation

- 4. Findings

- 5. Conclusions

- 6. Recommendations

- 7. Management Response and Action Plan

- APPENDIX A: Documents Reviewed

- APPENDIX B: Triaging by Cybertip.ca

- APPENDIX C: Projects Funded By the Contribution Program

- APPENDIX D: National Strategy Partnership Work

- APPENDIX E: NCECC'S Contribution to Child Sexual Exploittation Cases

- APPENDIX F: Financial Information

Note: [ * ] indicates severances made under the Access to Information and Privacy Act.

Executive Summary

Evaluation supports accountability to Parliament and Canadians by helping the Government of Canada to credibly report on the results achieved with resources invested in programs. Evaluation supports deputy heads in managing for results by informing them about whether their programs are producing the outcomes that they were designed to achieve, at an affordable cost; and, supports policy and program improvements by helping to identify lessons learned and best practices.

What we examined

The National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet (the National Strategy) is a horizontal initiative providing a comprehensive, coordinated approach to enhancing the protection of children on the Internet and pursuing those who use technology to prey on them. The evaluation covered the activities delivered under the National Strategy by Public Safety Canada, including: the Canadian Centre for Child Protection as a funding recipient for the management of the national tipline Cybertip.ca, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (through NCECC—National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre, a national division of the Canadian Police Centre for Missing and Exploited Children/Behavioural Sciences Branch) and the Department of Justice. The evaluation included the Contribution Program to Combat Child Sexual Exploitation and Human Trafficking and its administration by Public Safety Canada. The scope of the evaluation covered the time period over the past five years (July 2008 to December 2013).

Why it's important

The advent of the Internet has considerably facilitated child sexual exploitation behaviour, changing the way offences are committed, investigated and prosecuted, as well as the volume of these offences. Investigations into Internet-based child sexual exploitation are complex and often international in scope. The National Strategy aims to ensure national collaboration and to provide central coordination with regard to investigations, reporting of suspected cases, providing specialized training to law enforcement, public education and awareness, research, as well as cooperation with the international community.

What we found

Relevance

There is a continued need to address the sexual exploitation of children on the Internet. Evidence shows increasing trends in the number of reported offences, the availability of material and the severity of these criminal acts. The increasing use of the Internet, mobile technologies and social media have facilitated the sexual exploitation of children. Concerns about child pornography have extended to the availability of material on peer-to-peer networks, the “dark Web” and through encrypted technologies. The problem extends well beyond Canada's borders. Law enforcement faces increasing challenges posed by transnational child sex offenders in addition to online child sexual exploitation offences in general. These types of international investigations are appropriately characterized as increasingly complex.

The National Strategy remains relevant to ensure national collaboration and a consistent national approach, as well as cooperation with the international community. The evaluation points to a continued need for improved data collection, increased research efforts and enhanced information exchange at the national level in order to better understand the underpinnings and contributing factors surrounding online child sexual exploitation. There may be a need to revisit the current mandate as a number of areas of concern are expanding (e.g. transnational child sex offenders, self-peer exploitation or “sexting”, cyberbullying, sextortion, sexualized child modelling) that were not originally envisioned by the National Strategy. Increased public reporting continues to put resourcing pressures on the law enforcement community. There is also evidence to indicate that there is still a need to increase knowledge and awareness about Internet child sexual exploitation and that the issue needs to be addressed through a multi-faceted approach (e.g. socially through education and prevention, and complemented by law enforcement efforts).

The National Strategy aligns with federal priorities and the departmental mandates of the federal Strategy partners. The safety and security of children is central to the federal strategic priorities as reflected in numerous legislative initiatives, ministerial press releases, official documents and initiatives, and is consistent with the federal commitment made most recently in the 2013 Speech from the Throne.

The National Strategy aligns with federal legislative roles and responsibilities of Strategy partners and the broad role of the federal government in the safety and security of Canadians. Investigations cross jurisdictions and require the collaboration and coordination of many stakeholders nationally and internationally. There is an opportunity for PS to provide greater leadership at the national level in areas of cooperation and in facilitating data collection, research and information sharing. The National Strategy also supports international commitments aimed at combating child sexual exploitation on the Internet.

Evidence suggests that initiatives by other jurisdictions or non-profit organizations tend to complement the National Strategy. However, there may be opportunities for greater synergy and collaboration, especially between the federal government and provinces and territories in order to ensure that federal investments are targeted to areas of greatest need. In support of this, Strategy partners continue to develop partnerships with provinces, non-governmental organizations and private industry as well as participate in the Federal/Provincial/Territorial committees. From an enforcement perspective, the Strategy helps avoid duplication by providing a centralized coordinated approach and central point of contact for investigations that cross multiple jurisdictions nationally and internationally. Without a centralized coordinated approach, it was suggested that the system in Canada would be disparate. Despite the different organizations involved at various levels, efforts aimed at coordinating investigations internationally are seen as complementary rather than duplicative.

Performance

Public Reporting

Cases of online child sexual exploitation reported by the public to Cybertip.ca have been increasing for the past ten years, with a significant increase being noted in 2012-13. The National Strategy has contributed to this trend through activities aimed at enhancing public awareness and stimulating public reporting (e.g. awareness campaigns), as well as participation in high-profile investigations with provincial, municipal and international law enforcement agencies. It is likely that other factors, activities and actors outside of the National Strategy are also impacting general public awareness and reporting.

Coordinated approach

The National Strategy aimed to put in place a nationally coordinated approach to online child sexual exploitation investigations through centralized points of contact for public reporting (Cybertip.ca) and investigations (NCECC), as well as through other forms of law enforcement support. The evaluation found that the National Strategy has contributed to this outcome, but that gaps remain.

Canadian law enforcement agencies noted that while NCECC investigative packages generally offer useful information, delays in receiving packages have an adverse impact on the ability to conduct investigations in a timely manner. Delays were attributed to resource or staffing issues, an increase in the volume of reports, and backlog or operational issues. International law enforcement agencies find NCECC packages timely, accurate and complete. Cybertip.ca's triage function helped reduce Canadian law enforcement's processing burden and the reports provided have been timely and comprehensive. However, building on the positive work initiated through the new National Strategy working committee, closer cooperation is needed between Cybertip.ca and NCECC, and an examination is also warranted to determine how Cybertip.ca reports can best support NCECC's investigative work. Furthermore, the overall coordination and investigative process could benefit from a more formal and consistent feedback mechanism between Cybertip.ca, NCECC and Canadian law enforcement agencies regarding the status and result of investigations.

The National Strategy continues to deliver key benefits with respect to enhancing investigative coordination and supporting law enforcement agencies. Cybertip.ca supported law enforcement agencies with assistance and information for investigations. NCECC is seen to be an appropriate body for coordinating major national investigations and continues to play a critical role in facilitating the international component of investigations, despite concerns about capacity, which may potentially hinder efforts towards a nationally coordinated approach. Favourable views were held about NCECC training and assistance to law enforcement agencies, such as the categorization of child pornography material, victim identification and other operational support. Information technology systems continue to present a challenge to coordination efforts under the National Strategy, and challenges remain with regards to the establishment of an effective online child sexual exploitation tracking system for law enforcement agencies in Canada.

Supporting Children, Families and their Communities in Preventing Online Child Sexual Exploitation

The National Strategy has supported children, families and their communities through the education activities of the Canadian Centre for Child Protection. Materials developed by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection are widely distributed and referenced by law enforcement agencies and others (e.g. educators) in presentations and school programs. The Canadian Centre for Child Protection also delivered numerous awareness and education activities. Some of their educational programs report successful findings with regards to quality, usefulness and affecting change among participating organizations. Through these activities, it is likely that the Canadian Centre for Child Protection has contributed to enhancing awareness, encouraging reporting and educating parents, teachers and children about the risks of online child sexual exploitation, despite impact not being quantified and other factors also contributing to general awareness among Canadians. Evidence also shows that public awareness campaigns and publicity around enforcement actions routinely generate strong interest from the public in obtaining information and educational programs related to child sexual exploitation, which also suggests an enhanced level of awareness. Nonetheless, due to the evolving nature of online child sexual exploitation, there are still opportunities to increase public awareness, education and prevention.

Partnerships and Other Activities Supporting a National Approach

The National Strategy continues to support partnerships with national and international stakeholders, the private sector, the non-profit sector, and law enforcement counterparts that are important to achieving successful outcomes. These partnerships support investigative capacity building and/or awareness and education efforts and include training, knowledge and resource exchanges, workshops and national conferences.

Enhanced Protection of Children from Online Child Sexual Exploitation

The evaluation shows that efforts by National Strategy partners have contributed to the enhanced protection of children from sexual exploitation on the Internet. The Canadian Centre for Child Protection contributed through triaging tips, processing reports for investigation by law enforcement agencies, identifying Websites containing child pornography and through their outreach activities and materials. NCECC contributed by preparing investigative packages, coordinating national and international major cases, providing investigative support as well as investigative training. Several high profile cases leading to the rescue of victims and the arrest of suspects illustrate the contribution of the National Strategy.

Informing Policy and Legislative Development

The National Strategy is seen as an important instrument with activities that enhance the body of knowledge of online child sexual exploitation through research, reports and analysis. Studies have helped inform policy development; however, further and better integrated research is needed to guide policy, legislative changes, law enforcement approaches, and prevention and treatment strategies. The evaluation notes that, in exercising its leadership role, PS should explore opportunities for greater synergy and collaboration and involve a broader base of stakeholders to enhance the identification of policy and legislative issues and to develop a federal vision on Internet child sexual exploitation. This issue crosses over into several other related policy areas (e.g. human trafficking, cybercrime, cyberbullying). There is a need to strategically position child sexual exploitation to respond to political priorities and to ensure accountability.

Horizontal Governance and Performance Measurement

There is opportunity to strengthen overall coordination and governance of the Strategy. There have been improvements since a more formal committee was put in place in April 2013, bringing together PS, NCECC and the Canadian Centre for Child Protection. There are still challenges related to the availability of information and information sharing between partners. Key areas to address in the overall coordination of the Strategy include increased clarity and communication of roles and responsibilities of the various Strategy partners, stronger engagement of and closer partnerships with provincial stakeholders, and enhanced coordination between public awareness activities and operational response. Strategy activities should be guided by and aligned with a federal agenda. Finally, as identified in the previous evaluation, gaps remain related to performance measurement. The implementation of the performance measurement strategy, developed in 2013, will be instrumental in monitoring and gauging the performance related to each of the Strategy's expected outcomes.

Efficiency and Economy

Research indicates that sexual abuse of children results in very high costs to society over the long-term. This suggests that investments of public funds to combat such crimes, especially those involving sexual abuse, could have large economic benefits, potentially reaching several billion dollars annually.

PS demonstrated effective use of resources in managing the Contribution Program, and its funding recipient, C3P, also seems to be efficiently delivering activities and producing deliverables, both in terms of triage and educational material. The combination of increased demand for NCECC services, coupled with issues related to timeliness and a backlog have challenged NCECC efficiency in recent years. It should be noted that measures of efficiency do not reflect the increasing complexity of investigations.

In terms of use of allocated resources, PS and Justice generally expended allocations intended to be spent on National Strategy activities within expected limits, while RCMP expenditures fell short of their allocations by an average of 26% per year. This situation was also noted in the previous evaluation. Although over the course of the evaluation period, the amount lapsed has decreased to 18% in 2012-13.

Recommendations

The Internal Audit and Evaluation Directorate recommends that PS, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Justice, implement the following:

- PS should examine opportunities to enhance its leadership, governance and horizontal coordination efforts, in collaboration with RCMP and Justice as appropriate, to align with the government's policy direction and federal vision for the National Strategy.

- PS and RCMP should examine current process to identify potential causes to NCECC's difficulty in pursuing Cybertip.ca reports, and take corrective actions deemed necessary.

- The RCMP should examine the causes to the lack of timeliness of NCECC services. This could involve a mapping of processes within NCECC and between NCECC, Cybertip.ca and/or law enforcement agencies and the examination of resource use and allocation of funding intended to address online child sexual exploitation. PS should facilitate Cybertip.ca's involvement as required.

- The RCMP should work with its national and international police partners in terms of implementing a technological solution as an alternative to CETS in order to meet the needs of law enforcement users to facilitate national coordination of child sexual exploitation investigations, information and intelligence sharing and avoid duplication.

- All Strategy partners should proactively collect and report performance information as laid out in the Performance Measurement Strategy, including the results of prevention activities and enforcement actions. Stronger engagement of provincial/municipal law enforcement agencies is required to collect information.

Management Response and Action Plan

Strategy partners accept all recommendations and will implement an action plan

1. Introduction

This is the Public Safety Canada (PS) 2013-14 Evaluation of the National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet (herein referred to as the National Strategy or simply the Strategy). This evaluation provides Canadians, parliamentarians, Ministers, central agencies, and the Deputy Minister of Public Safety with an evidence-based, neutral assessment of the relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of this federal government horizontal initiative.

2. Profile

2.1 Background

The exploitation of children, particularly sexual exploitation, is not a new phenomenon. However, the advent of the Internet has considerably facilitated such criminal behaviour, changing the way child sexual exploitation offences are committed, investigated and prosecuted, as well as the volume of these offences. Investigations into Internet-based child sexual exploitation are complex and often international in scope. Indeed, the Internet and related online technologies can provide borderless and easy access to large quantities of electronically available images, videos and audio recordings of children being sexually exploited.

The National Strategy was launched on April 1, 2004 as a horizontal initiative bringing together Public Safety Canada (PS), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), and Industry CanadaFootnote 1 to provide a comprehensive, coordinated approach to enhancing the protection of children on the Internet and pursuing those who use technology to prey on them. In February 2009, the National Strategy was renewed and allocated approximately $8 million per year in ongoing funding. Also at this time, PS created the Contribution Program to Combat Child Sexual Exploitation and Human Trafficking (herein, the Contribution Program) to support initiatives, research, partnership building, projects and programs to advance efforts to combat online child sexual exploitation and human trafficking. The 2007 Federal Budget had also allocated ongoing funding of $6 million per year to advance efforts to combat child sexual exploitation and human traffickingFootnote 2. Justice Canada started receiving funding in 2007 to provide training, legal advice and support to National Strategy partners.

2.2 Objectives of the National Strategy

Program objectives for the 2009 to 2014 period included:

- providing a focal point where the public can report suspected cases of child sexual exploitation on the Internet including, through an ongoing contribution to the Canadian Centre for Child Protection, which manages Cybertip.ca, the national tipline;

- enhancing/reinforcing law enforcement capacity including the creation of a database to prioritize and focus on the identification and rescue of child victims;

- providing for public education and awareness, including providing for public education and reporting of cases of child sexual exploitation on the Internet;

- solidifying networks with private and public sectors, and non-governmental organizations; and,

- providing coordination, oversight and research on online child sexual exploitation.

2.3 Federal PartnersFootnote 3

Public Safety Canada

PS is the lead department for the National Strategy, and is responsible for:

- coordinating and overseeing the continued implementation of the Strategy;

- managing the Contribution Program, including a contribution agreement with the Canadian Centre for Child Protection;

- coordinating research and reporting;

- monitoring current and proposed legislation;

- developing policies that will help combat child sexual exploitation on the Internet; and,

- participating in international fora to discuss and coordinate policy on issues related to international policy on child sexual exploitation.

As a PS contribution recipient, the Canadian Centre for Child Protection takes part in the National Strategy by operating the national tipline Cybertip.ca and by developing and distributing public awareness and educational material to various target groups in Canada. For the purpose of the evaluation, the Canadian Centre for Child Protection was considered a Strategy partner. Throughout this report, “Cybertip.ca” is used when referring to the national tipline, while “C3P” designates the Canadian Centre for Child Protection in relation to its other activities such as public awareness and education.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police

As part of the National Strategy, the RCMP is responsible for disseminating information and intelligence on national and international online child sexual exploitation cases. These cases are very complex as they are often multi-jurisdictional, involve several suspects, embody a significant amount of technological evidence, and can include numerous victims. The RCMP has the ability to respond immediately to a child at risk in Canada or internationally. The RCMP mandate in this area is to reduce the vulnerability of children to Internet-facilitated sexual exploitation by identifying victimized children, investigating and assisting in the prosecution of sexual offenders; and, strengthening the capacity of municipal, territorial, provincial, federal and international police agencies through training, operational research, and investigative support. .

The activities are carried out by the Canadian Police Centre for Missing and Exploited Children/Behavioural Science Branch (CPCMEC/BSB), more specifically the National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre (NCECC) and other units providing victim identification support, specialized training and research services. For the purpose of this evaluation report, “NCECC” is used to designate all activities of these units funded as part of the National Strategy.

Department of Justice

Justice Canada received ongoing support for one full time equivalent to provide for training, legal advice and support to federal partners of the National Strategy. Justice Canada liaises with Strategy partners and reviews legislation to ensure it remains representative of the environment.

2.4 Resources

Table 1 illustrates the ongoing yearly funding for each federal organization that delivered Strategy activities from 2008-09 to 2012-13.

Table 1: Ongoing Yearly Funding Allocation ($ million)* |

|

|---|---|

| PS | $0.5M |

| Contribution Funding | $1.9M |

| RCMP | $7.9M |

| Justice | $0.2M |

| Total | $10.5M |

* Figures are net amounts and do not include amounts for Employee Benefits Plan, Public Works and Government Services Canada accommodations, or internal services charges.

2.5 Logic Model

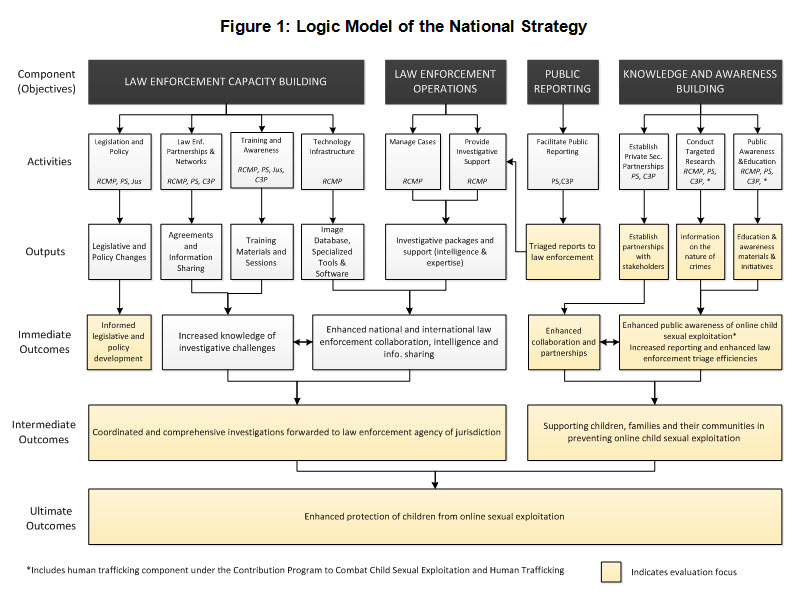

The logic model presented in Figure 1 is a visual representation that links what a program is funded to do (activities) with what the program produces (outputs) and what the program intends to achieve (outcomes). It also provides the basis for developing the evaluation matrix, which gave the evaluation team a roadmap for conducting this evaluation. Highlighted items indicate the focus of the evaluation.

Image Description

The Strategy logic model has 4 components (objectives): Law enforcement capacity building; Law enforcement operations; Public reporting; and Knowledge and awareness building.

The following describes activities and outputs for Law enforcement capacity building:

Activity A: legislation and policy (RCMP, PS, JUS) leads to output 1: legislative and policy changes.

Activity B: law enforcement partnerships and networks (RCMP, PS, C3P) leads to output 2: agreements and information sharing.

Activity C: training and awareness (RCMP, PS, JUS, C3P) leads to output 3: training materials and sessions.

Activity D: technology infrastructure (RCMP) leads to output 4: image database, specialized tools & software.

The following describes activities and outputs for Law enforcement operations:

Activity E: manage cases (RCMP) and activity F: provide investigative support (RCMP) lead to output 5: investigative packages and support (intelligence & expertise).

The following describes activities and outputs for public reporting:

Activity G: facilitate public reporting (PS, C3P) leads to output 6: triaged reports to law enforcement. This output also contributes to activity F: provide investigative support (RCMP).

The following describes activities and outputs for Knowledge and awareness building:

Activity H: establish private sector partnerships (PS, C3P) leads to output 7: establish partnerships with stakeholders.

Activity I: conduct targeted research (RCMP, PS, C3P) leads to output 8: information on the nature of crimes.

Activity J: public awareness and education (RCMP, PS, C3P) leads to output 9: education & awareness materials & initiatives.

Note: Activities I and J include the human trafficking component under the Contribution Program to Combat Child Sexual Exploitation and Human Trafficking.

Output 1 (legislative and policy changes) leads to immediate outcome 1: informed legislative and policy development.

Output 2 (agreements and information sharing) and output 3 (training materials and sessions) lead to immediate outcome 2: increased knowledge of investigative challenges.

Output 4 (image database, specialized tools & software.) and output 5 (investigative packages and support) lead to immediate outcome 3: enhanced national and international law enforcement collaboration, intelligence and information sharing.

Immediate outcomes 2 and 3 contribute to one another.

Output 7 (establish partnerships with stakeholders) leads to immediate outcome 4: enhanced collaboration and partnerships.

Output 8 (information on the nature of crimes) and output 9 (education & awareness materials & initiatives) lead to immediate outcome 5: enhanced public awareness of online child sexual exploitation (includes the human trafficking component under the Contribution Program to Combat Child Sexual Exploitation and Human Trafficking); increased reporting and enhanced law enforcement triage efficiencies.

Immediate outcomes 4 and 5 contribute to one another.

Immediate outcomes 1, 2 and 3 contribute to the following intermediate outcome: Coordinated and comprehensive investigations forwarded to law enforcement agency of jurisdiction.

Immediate outcomes 4 and 5 lead to the following intermediate outcome: supporting children, families and their communities in preventing online child sexual exploitation.

Intermediate outcomes lead to the following ultimate outcome: enhanced protection of children from online sexual exploitation.

The evaluation mainly focused on the following:

Output 6: triaged reports to law enforcement.

Output 7: establish partnerships with stakeholders.

Output 8: information on the nature of crimes.

Output 9: education & awareness materials & initiatives.

Immediate outcome 1: informed legislative and policy development.

Immediate outcome 4: enhanced collaboration and partnerships.

Immediate outcome 5: enhanced public awareness of online child sexual exploitation; increased reporting and enhanced law enforcement triage efficiencies.

Intermediate outcomes: coordinated and comprehensive investigations forwarded to law enforcement agency of jurisdiction; and supporting children, families and their communities in preventing online child sexual exploitation.

Ultimate outcome: enhanced protection of children from online sexual exploitation.

3. About The Evaluation

3.1 Objective

This evaluation supports:

- Accountability to Parliament and Canadians by helping the Government to credibly report on the results achieved with resources invested in this program;

- The Deputy Minister of Public Safety in managing for results by providing information about whether this program is producing the outcomes that it was designed to produce, at an affordable cost; and,

- Policy and program improvements.

3.2 Scope

The scope of the evaluation mainly covered the time period over the past five years (2008-2009 to 2012-2013), beginning after the previous evaluation was completed (dated July 2008). Some performance data from 2013-2014 (up to December 2013) was also assessed.

As required by the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation, the evaluation determined the relevance of the Initiative: continued need; alignment with government priorities; and, consistency with federal roles and responsibilities. The evaluation also examined the performance of the Initiative: the achievement of expected outcomes; and, a demonstration of efficiency and economy.

3.3 Methodology

The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation, the Directive on the Evaluation Function; the Standard on Evaluation for the Government of Canada; and the Guidance on the Governance and Management of Evaluations of Horizontal Initiatives. The evaluation was a goal-based, implicit design, and evaluators took into account the following factors in order to calibrate the evaluation effort, including the approach, scope, design and methods:

- Risks;

- Quality of past evaluations;

- Soundness of program theory;

- Longevity of the program; and,

- Contextual stability.

3.3.1 Evaluation Core Issues and Questions

As required by the Directive on the Evaluation Function, the following issue areas and evaluation questions were addressed in the evaluation:

Relevance

1. How has the National Strategy evolved to meet new or changing needs?

2.

a) To what extent does the National Strategyalign with the policy priorities of Government?

b)

To what extent does the National Strategysupport the strategic outcomes of the partners?

a) To what extent is the National Strategy aligned with federal government roles and responsibilities?

b) Does the National Strategy duplicate or overlap with other programs, policies or initiatives delivered by other stakeholders?

Performance—Effectiveness

4. To what extent has the National Strategy achieved expected outcomes in terms of:

a)

coordination of investigations (including law enforcement collaboration, intelligence and information sharing; knowledge and awareness among criminal justice partners; and triage function)

b)

informing legislative and policy development

c)

support to children, families and their communities in preventing online child sexual exploitation (including enhanced public awareness; increased public reporting; and partnerships)

d)

protection of children from online sexual exploitation

5. To what extent does the horizontal approach contribute to or detract from the achievement of outcomes?

Performance—Efficiency and Economy

6. To what extent have National Strategy partners minimized the use of resources in realizing outputs and outcomes?

3.3.2 Lines of Evidence

The evaluation team used the following lines of evidence to conduct the evaluation: document review, interviews, and a review of performance and financial data. Each of these methods is described in more detail below.

Document Review

The document review included the following types of documents: reviews, evaluations, corporate, accountability and policy documents, inception documents, reports on plans and priorities, speeches from the Throne, and legislative documents, program documents (i.e. terms of reference, records of discussion and record of decisions). A list of documents reviewed is presented in Appendix A.

Literature Review

The literature review included publicly available research studies and reports to provide context on current trends and knowledge surrounding child sexual exploitation on the Internet. The documents reviewed are included as part of Appendix A.

Interviews

In total, 19 interviews were conducted. Interviewees included program representatives, C3P, law enforcement agencies in Canada (8) and abroad (3) and Internet Service Providers.

Review of Financial and Performance Information

An analysis of performance data included the examination of program output and outcome data, as well as evaluations conducted internally by C3P and final project reports from funded recipients. The financial analysis included the assessment of program budget and expenditure information and the cost to the federal government.

3.4 Limitations

The following section describes data limitations and how the evaluation team addressed these limitations.

- Qualitative information from interviews only represents the viewpoints of selected interviewees. Where possible, the evaluation aimed to address this limitation by supplementing interview information with quantitative information and document review.

- Performance data was gathered using a template for each partner. In some cases, no performance data had been collected on an ongoing basis, contrary to the existing Results‑Based Management Accountability Framework (RMAF). Strategy partners developed a Performance Measurement Strategy in March 2013, a few months prior to the start of the evaluation.

- C3P is a non-government charitable organization funded under the National Strategy to manage the national tipline Cybertip.ca and to develop and deliver awareness and education material and activities. C3P also receives funding from other organizations, e.g. provincial governments and private sector. Therefore, results of the work of C3P (e.g. distribution of education material, impact on public awareness and knowledge among target audiences) cannot be solely attributed to the National Strategy and must also be shared with other funding organizations. Furthermore, data on education material downloads and Website page views may not represent unique visitors and should be interpreted within this context.

- The funding recipient (e.g. C3P) from PS's Contribution Program to Combat Child Sexual Exploitation and Human Trafficking conducted internal evaluations of their activities and projects to assess effectiveness and impact. The objectivity and validity of these evaluations could not be verified.

- Investigations into alleged cases of online child sexual exploitation are predominantly carried out by provincial and municipal law enforcement agencies (or by the RCMP in carrying out provincial police services under contract police agreements). Therefore, individuals arrested and victims rescued cannot be solely attributed to the National Strategy. As much as possible, the evaluation aimed to highlight the contribution of Strategy partners to investigations.

- The evaluation included a review of cases coordinated by NCECC. The evaluation included a small sample of files selected by NCECC that reasonably represented their work. Therefore, the results of the file review should not be considered representative of all files, as each differs widely in terms of quantity of evidence, complexity and technological sophistication.

- In conducting the financial analysis, it was not always possible to isolate funding associated with some specific Strategy activities. Therefore, estimates and assumptions were made in conjunction with the financial management advisors and program representatives from each federal participating organization.

- The mitigation strategy for the above methodological limitations was to use multiple lines of evidence that included both quantitative and qualitative data from a range of sources to answer evaluation questions in an effort to triangulate findings from these different sources.

3.5 Protocols

During the conduct of the evaluation, program representatives from PS, the RCMP and Justice Canada in collaboration with their respective evaluation units, assisted in the identification of key stakeholders and provided documentation and data to support the evaluation. Collaborative participation greatly enriched the evaluation process.

This report was submitted to evaluation representatives and program representatives (up to the Director General level) of each partner organization. The report was then sent to the responsible Program Heads (Assistant Deputy Minister level) for review and acceptance. A management response and action plan was prepared in response to the evaluation recommendations by each organization, where appropriate. These documents were submitted to Departmental Evaluation Committees, Deputy Heads and/or Heads of Evaluation for approval, before being presented for consideration and final approval by the Deputy Minister of Public Safety Canada.

4. Findings

4.1 Relevance

4.1.1 Need for the National Strategy

The evaluation examined the issue of continuing need from two perspectives: 1) whether online child sexual exploitation still persists and needs to be addressed; and 2) whether the need for the National Strategy persists and how the Strategy has evolved to adapt to new or changing trends.

Evidence demonstrates that there is a continued need to address the sexual exploitation of children on the Internet given its exponential growth. There are increasing trends in the number of reported offences, availability of materials due to emerging technologies and the severity of these criminal acts. The Internet has broadened the scope of child sexual exploitation by facilitating direct, anonymous contact between children and adults.Footnote 4 The NCECC reported in 2007 that thousands of new images or videos are put on the Internet every week and hundreds of thousands of searches for child sexual abuse images are performed daily.Footnote 5 The general view from interviewees is that there is a substantial increase in child sexual exploitation on the Internet, demonstrated by an increase in the number of reports/tips, files and investigations. However, as suggested by some, it is not known whether this increase is due to heightened attention on this issue over the past decade and efforts to detect and investigate or whether it is due to an actual increase in the incidence of cases. Nonetheless, reports from the public to Cybertip.ca have been increasing since the tipline was established in 2002. The NCECC has also seen an increase in the number of reports it received from international and national agencies (e.g. a 60% increase in the number of suspected child sexual exploitation reports and assistance requests from 2010-11 to 2012-13).

Interviewees agreed that the increase in reported cases of online child sexual exploitation is linked to the growth of Internet use and constantly evolving technologies, such as mobile devices. For example, from 2009-10 to 2011-12, Cybertip.ca registered a 214% increase in the number of reports concerning mobile devices.Footnote 6The effect of technology is twofold; on the one hand, new technologies provide law enforcement with more effective tools to track offenders. On the other hand, networks of offenders use increasingly secure methods to distribute child sexual abuse materials over the InternetFootnote 7(e.g. clouding, peer-to-peer networks, dark Web, Tor anonymity network, encryption software). Interviewees also noted the increase in the volume of seizures (offenders may have over a million child sexual abuse imagesFootnote 8). Accessing and processing all this potential evidence is a key challenge for law enforcement.

Research suggests that 13% to 19% of children and youth from the general population have had an experience of online sexual exploitation.Footnote 9 Child sexual exploitation victims, mostly girls, are increasingly younger and images are more violent.Footnote 10 In 82% of the images analyzed by Cybertip.ca in 2012, children are under 12 years of age (57% of those are under 8 years of age).Footnote 11 The number of images of “serious child abuse” quadrupled between 2003 and 2007.Footnote 12 Some study findings aim to demonstrate the link between viewing child pornography and offending and suggest that more than half of child pornography offenders either abuse or attempt to abuse children.Footnote 13 Offenders' compulsive Internet usage and online networks of abusers may fuel hands-on offending against children and young people.Footnote 14

The problem extends well beyond Canada's border. Troels Oerting, head of the European Cybercrime Centre at Europol, stated that “as technology further develops and previously under-connected parts of the world come online, we can expect to see new offenders, new victims, and new means of committing crimes against children”Footnote 15. Interviewees noted the challenges posed by child sex tourism and travelling child sex offenders as they seek out jurisdictions with less stringent laws or oversight. There seems to be an increasing number of international cases, and investigations are increasingly interlinked and complex. Interviewees explained that this trend is very much linked to the opportunities created by emerging technologies such as mobile Web and the increasing use of social media to exchange images.

One clear emerging trend noted by most interviewees was self-peer exploitation (sexting) and its link to cyberbullying. This problem is escalading as teens are heavy users of the Internet, social media and mobile devices. This type of activity has increased the burden on law enforcement (one interviewee noted that it can take up to half of investigative time) and therefore the need for greater screening and prioritization. It is also challenging as evidence of criminal activity may, in some cases, be less apparent. Sexualized child modeling was also noted as an increasing trend.

Evidence demonstrates that the need for the National Strategy persists to ensure national collaboration and a consistent national approach to broadly address child sexual exploitation on the Internet as well as cooperation with the international community. This is demonstrated by a need to centralize information and coordinate in key areas (i.e. investigations, awareness, research).

In its 2011 report on child sexual exploitation, the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights noted that “many initiatives to combat child sexual exploitation are carried out in isolation; and that programs are inconsistently available across the country and often lack the means to coordinate efforts or exchange information and best practices. Therefore, there is a need for the Government to work with provinces and territories to facilitate greater awareness and coordination of existing programs”.Footnote 16 This speaks to the need for a coordinated strategy, the role of the federal government and the way the Strategy complements work being undertaken in the provinces and territories.

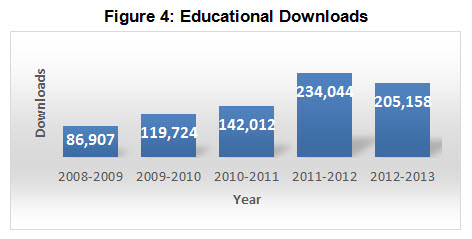

The need to increase knowledge and awareness about online child sexual exploitation was frequently mentioned by interviewees. Respondents say that online child sexual exploitation needs to be addressed as a social issue, not simply a policing one. NCECC and C3P receive many requests for awareness presentations (from non-governmental organizations, international organizations). Between 2008-09 and 2012-13, C3P received more than 3,300 direct requests for educational material, Internet safety information, and referral services. Additionally, there were more than 200,000 downloads of educational material from Websites administered by C3P in 2011-12 and 2012-13. Education and prevention were also areas identified by the Standing Senate Committee for possible federal government involvement.

Law enforcement agencies were concerned that, as public awareness and reported cases increase, resourcing may become an issue. Another problem for law enforcement is accessing information about suspects, identifying children and preventing future abuse.Footnote 17 Therefore, interviewees stated the importance of continued work with Internet service providers.

There is also a need to improve data collection and research at a national level. The Senate Standing Committee pointed to a lack of data and statistics regarding the extent of the problem.Footnote 18 A few interviewees stressed that more research is needed to understand the underpinnings and causal factors surrounding online child sexual exploitation. Research is seen to be needed to guide policy, legislative changes, law enforcement approaches, and prevention and treatment strategies. The Committee recommended that a national databank of research and statistical information be developed in cooperation with key stakeholders and be made publicly accessible.

In terms of the Strategy's ability to adapt to new trends, many interviewees felt that the Strategy has been adapting and evolving to emerging trends while some say that it is slow to react and has not evolved much. Strategy partners are exploring ways to address new trends, for example through research. The Strategy seems to be flexible enough to adapt to new trends; however, there may be a need to revisit the current mandate as a number of areas of concern are expanding (e.g. travelling child sex offenders, self-peer exploitation or “sexting”, cyberbullying, sextortion, sexualized child modeling) that were not originally envisioned. Interviewees mentioned a few areas that could be addressed by the Strategy: more engagement with provinces and municipalities, sharing best practices, training for police officers and research on officer wellness.

Finally, the Canadian public is highly supportive of actions to address online child sexual exploitation. More than 90 percent of Canadians are concerned about the issue and it is ranked as one of the top three concerns for parents regarding children.Footnote 19

4.1.2 Alignment with Governmental Priorities

The evaluation sought to assess the degree of alignment of the National Strategy with federal government priorities and departmental strategic outcomes mainly through document review.

Over the past five years, the Government of Canada has consistently underlined the fight against child sexual exploitation as a priority. Speeches, official public documents, and press releases identify the fight against online child sexual exploitation as one of the main priorities for the Canadian government.

The 2013 Speech from the Throne stated that the Government of Canada will focus on “protecting the most vulnerable of all victims, our children” with emphasis on the non-consensual distribution of intimate images. In August 2013, the Prime Minister announced that the federal government would introduce tough new penalties for those convicted of sex offences involving children. On February 26, 2014, the Tougher Penalties for Child Predators Act was introduced by the Minister of Public Safety and the Minister of Justice. The Act included nine key measures designed to better protect children from a range of sexual offences and exploitation at home and abroad.

In recent years, the federal government has brought forward a number of legislative initiatives, such as Bill C-22, an Act respecting the mandatory reporting of Internet child pornography by persons who provide an Internet service, received Royal Assent in March 2011. Service providers covered by the Act now have certain obligations to report online child pornography. Bill C-10, Safe Streets and Communities Act received Royal Assent in March 2012. It introduced comprehensive legislation, which included proposed reforms to the Criminal Code designed to protect children from sexual predators. Bill C-13, Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act, was prompted by several high profile cases of cyberbullying. This proposed legislation (November 2013) would make the distribution of sexually explicit images without a person's consent a criminal offence.

The National Strategy is aligned with the departmental mandates of the federal Strategy partners. The 2013-14 PS Report on Plans and Priorities states that “Public Safety Canada will continue to implement the […] National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet, including in the area of Canadian travelling child sex offenders.” The 2012-13 RCMP Report on Plans and Priorities states that “particular focus will be directed at combating Internet-facilitated child sexual exploitation by building capacity for specialized investigative technologies, victim identification, international training, and facilitating intelligence and information sharing between Canadian and international police agencies.” From 2010 to 2014, the Department of Justice's Reports on Plans and Priorities stated that the department would support the passage of legislative initiatives to better protect children from sexual offenders.

4.1.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The evaluation sought evidence of accountability and authority to deliver the National Strategy to understand whether there is alignment with the federal role.

The National Strategy aligns with federal roles and responsibilities with regard to legislation. The Constitution Act, 1867, provides exclusive legislative authority to the federal government in all matters related to the criminal lawFootnote 20 whereas enforcing the Criminal Code is considered to be primarily the responsibility of provincesFootnote 21. In keeping with this division, provinces and territories are the primary leads with respect to investigations and prosecutions of online child sexual exploitation related offences.

The federal government has a broad role in the safety and security of Canadians. Initiatives such as the National Strategy help advance federal policy objectives and priorities.

Internet-facilitated child sexual exploitation is a result of the modern digital world and crosses many jurisdictions.Footnote 22 Jurisdictional limits on individual police forces, the division of investigative responsibility when crimes cross these jurisdictional lines, and constraints on funds and manpower limit the ability of any single police force to carry out complex investigations.Footnote 23 These investigations require the collaboration and coordination of many stakeholders within the public safety, justice and law enforcement communities in Canada and also internationally.

As the national police force, the RCMP mandate is multi-faceted. Provincial and municipal police forces often rely on the RCMP to provide highly specialized police support services. The work of NCECC under the National Strategy aligns with the functions of the RCMP's National Police Services, which are the largest and often sole provider of specialized investigational support services to over 500 law enforcement and criminal justice agencies across Canada. National Police Services include numerous centres of expertise, such as NCECC, providing support on identification services, technological/technical investigations and support, enhanced learning opportunities, and the collection and analysis of criminal information and intelligence.Footnote 24 The aim is to enable and sustain uniform access to information that supports public safety and the administration of justice.

The RCMP is also part of the PS Portfolio, reporting to the Minister of Public Safety. PS plays a key role in discharging the Government's fundamental responsibility for the safety and security of its citizens. Under the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Act, the Minister is responsible for exercising national leadership relating to public safety and, as part of its Portfolio coordination and leadership duties, for coordinating the activities of PS Portfolio agencies and establishing strategic priorities relating to public safety for those organizations. The Minister may also implement public safety programs, enter into contribution agreements and cooperate with provinces or other Canadian and international entities. The Department's work under the National Strategy is consistent with these functions.

Under the Department of Justice Act, the role of the Minister of Justice and Attorney General is to provide legal services to the federal government. The Attorney General of Canada shall advise the heads of the departments of the Government on all matters of law connected with these departments. Such matters would include online child sexual exploitation covered by the National Strategy.

Finally, the National Strategy supports the federal government's international obligations under the G8 Strategy to Protect Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet, the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography and the Global Alliance Against Child Sexual Abuse Online.

4.1.4 Complementarity/Duplication of Effort

The evaluation sought to determine whether the efforts of the National Strategy are duplicated or complemented by other initiatives, through interviews and document review.

Most provinces have implemented specific activities or measures to address online child sexual exploitation.Footnote 25 Some provinces, such as Ontario and Manitoba, have formal comprehensive provincial strategies. Provincial efforts largely focus on public awareness, education and prevention; expanding police capacity; and creating partnerships with community organizations and government agencies. Most provinces have dedicated provincial or municipal child sexual exploitation investigative units, referred to as Internet Child Exploitation (ICE) units. At least one province has specialized Crown prosecutors for this type of cases.

Some non-government organizations, other than C3P, are also active in raising public awareness and education. Organizations such as Beyond Borders and OneChild work to raise awareness and develop partnerships and/or conduct research to address online child sexual exploitation.

These strategies, whether undertaken by provinces or by non-governmental organizations, were seen by interviewees as complementing the federal strategy; the general view being that overlap may exist, but is deemed necessary or beneficial. This presents a risk to federal investments targeting the greatest need areas. C3P has partnerships with provinces, non-governmental organizations and private industry (e.g. Disney) to assist them in developing and tailoring educational products. PS participates on various Federal/Provincial/Territorial working groups and fora (e.g. Coordinating Committee of Senior Officials, Criminal Justice), which provides the opportunity to find synergies and avoid duplication. Despite this, the PS program noted that while it is aware that provinces are doing work in this area; they have limited knowledge on specific activities undertaken. The Strategy would benefit from gaining a better understanding of the various provincial and territorial initiatives in order to guide federal involvement in complementing these different initiatives. This would also be consistent with the Standing Senate Committee findings highlighting the need for better national coordination.

From an enforcement perspective, interviewees stated that the Strategy provides a central point of contact for investigations. Without a centralized coordinated approach, it was suggested that the system in Canada would be disparate. Despite the different organizations involved at various levels, efforts aimed at coordinating investigations internationally are seen as complementary rather than duplicative.

4.2 Performance—Effectiveness

In order to assess the extent to which the National Strategy is achieving the performance related outcomes, the evaluation team examined different lines of evidence including: documents, reports and data provided by the Strategy partners as well as qualitative input from interviewees. The following sections present the key findings for the main outcomes that were the focus of this evaluation.

4.2.1 Public Reporting

An immediate outcome of the National Strategy is to increase public reporting of child sexual exploitation activity on the Internet. In this regard, C3P plays a major role in generating awareness and educating the public about online child sexual exploitation and encouraging public reporting by providing a reporting mechanism through the Cybertip.ca tipline.

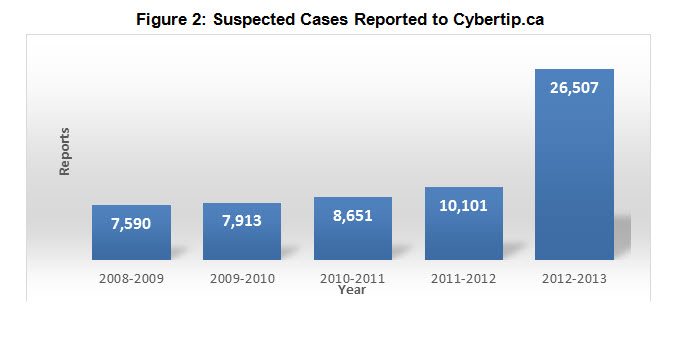

Over the five-year evaluation period, C3P data indicate that a total of 60,762 suspected casesFootnote 26 of child sexual exploitation were reported by the public to Cybertip.ca, which represents a significant increase (143%) from the previous evaluation period. The vast majority of cases were child pornography casesFootnote 27 (95%), while the remaining cases included a mix of child luring, child sex tourism, child prostitution, child trafficking and other offences.

Over this same 5-year period, the number of reports from the public increased each year, by an average of 9% between 2007-08 and 2011-12Footnote 28, followed by a dramatic rise of 162% in 2012‑13 (from 10,101 to 26,507 reports). Cybertip.ca attributes this increase to several factors, including: growing awareness of Cybertip.ca among the public and law enforcement, and more reporting from international hotlines and Web service providers.

Image Description

The graph shows the suspected cases reported to Cybertip.ca by fiscal year: in 2008-2009 7,590 cases reported; in 2009-2010, 7,913 cases reported; in 2010-2011, 8,651 cases reported; in 2011-2012, 10,101 cases reported; and in 2012-2013, 26,507 cases reported.

C3P also conducted 15 awareness campaignsFootnote 29 aimed at raising awareness and stimulating public reporting. Data provided by C3P indicate an increase in reporting during or in the immediate aftermath of each campaign. For example, the Help These Kids campaign generated a 10% increase in reporting, while two separate I Reported It campaigns generated a 50% and a 42% increase respectively, during or immediately following these awareness activities. It is important to note that these campaigns are not solely funded by the National Strategy (i.e. other public and private organizations also provide funding); therefore results should not be fully attributed to the Strategy.

Data and interviewee perceptions suggest that public reporting is also impacted by publicity surrounding high-profile and widely publicized enforcement actions. For example, in the week following the announcement of the results of Project SpadeFootnote 30 in November 2013, C3P experienced a 48% increase in reports submitted by the public and a 144% increase in reports submitted with information on a child victim and/or suspect.

4.2.2 Coordinated Approach to Online Child Sexual Exploitation Investigations

The National Strategy recognizes that a comprehensive and coordinated effort by all partners and stakeholders is needed to successfully combat Internet-based child sexual exploitation. A coordinated approach is one that embraces many aspects of the Strategy, such as triage and reports, investigations, support to law enforcement agencies, training and IT infrastructure. Therefore, the evaluation examined these aspects in assessing the establishment of a coordinated approach to online child sexual exploitation investigations in Canada.

Cybertip.ca triage and reports

Cybertip.ca processes all tips received from the public to determine potential illegal content or activity and to provide adequate classification of incidents contained in the reports (a report may contain several incidents). Once reviewed and classified, those reports that are deemed to contain illegal content are passed along by Cybertip.ca to the appropriate law enforcement jurisdiction in Canada, to NCECC or to another international tipline. Those reports wherein the jurisdiction is unknown or where complexity is greater, e.g. involving multiple jurisdictions, are sent to the NCECC. These cases require significant investigative time by the NCECC due to their increased complexity.

Data provided by Cybertip.ca shows that 55% of all reports received by the tipline involve legal content or require an educational response, and therefore are not passed along to law enforcement agencies. Of the remaining 45%, about half is sent to Canadian law enforcement agencies, including NCECC, while the other half is sent to international tiplines. In concrete terms, of the 60,762 reports received by Cybertip.ca from 2008-09 to 2012-13, approximately 20% (11,587 reports) were forwardedFootnote 31 to law enforcement agencies in Canada, mostly to NCECC. Some triaging examples are provided in Appendix B. These demonstrate how Cybertip.ca's triage function helped reduce law enforcement's processing burden by adequately identifying the lead law enforcement agency or by forwarding reports to NCECC for further assessment and determination of appropriate law enforcement of jurisdiction.

Interviewees consider Cybertip.ca's triage function to be both effective and efficient. Interviewees generally give Cybertip.ca good marks for triage performance, relevant analysis and risk assessment. The centralized function is also described as saving time and money resulting in more efficient investigations. Cybertip.ca reports contain, as available, information about the incident (e.g. type, date, location, etc.), the victim and suspect, the Website, as well as supplemental information (e.g. gleaned from additional open source online searches). Information from the tipster was seen to be paramount to supporting investigations. Respondents consider reports by Cybertip.ca to be both timely and comprehensive. It was noted, for example, that reports are of excellent quality and usually sent within 48 hours (as they do not require in-depth police investigation). However, some interviewees said that Cybertip.ca reports can be lengthy or repetitive, which makes processing these reports time consuming. Cybertip.ca was aware of these concerns and presented evidence demonstrating it has taken steps to address them (e.g. streamlining processes and reports) through its Law Enforcement Advisory Committee.

The evaluation also found that NCECC is having difficulty actionningFootnote 32 a high percentage of files incoming from Cybertip.ca. A detailed case review to determine the source and causes of this issue could not be completed as part of this evaluation. However, some possible explanations were put forward, one of them being that NCECC is unable to action files in the absence of actual child pornography pictures or videos as supporting evidence, which Cybertip.ca cannot lawfully store and forward. This issue was subject to consultation and a decision was made to maintain Cybertip.ca's current status in relation to storing and forwarding evidence. NCECC noted that information received from Cybertip.ca that does not generate an active investigation is bulk filed for intelligence purposes, divided by location, and sent to that particular local, provincial, or international law enforcement agency for their attention.

Additionally, URLs leading to child pornography material change rapidly from the time they are analyzed by Cybertip.ca and the time they are processed by NCECC; therefore, these URLs would become inactive between that time. It is unclear at what point in the process this issue arises. Cybertip.ca average processing times for 2012-13 range from 4 minutes to 302 minutes (approximately 5 hours), based on the priority of the file and the availability of information. Interviewees stated that C3P and NCECC need to find ways to work better together within these existing legal constraints. To this end, a Working Committee chaired by PS was established in April 2013 and “things are moving forward over the last six months”. Given that these findings vary considerably from the views expressed by other Canadian law enforcements agencies, the Strategy would benefit from a deeper examination into this issue.

Furthermore, it was suggested that the coordination and investigative process could benefit from a more formal and consistent feedback mechanism regarding the status and result of investigations, which would keep NCECC, Cybertip.ca and law enforcement agencies informed about the progress, conclusion and outcome of investigations.

NCECC triage and investigative packages

As the national law enforcement coordination center, the NCECC receives reportsFootnote 33 from the Cybertip.ca, as well as reports and requests for assistanceFootnote 34 from law enforcement agencies in Canada, the U.S.Footnote 35 and other countries. The number of suspected child sexual exploitation reports and assistance requests received by NCECC increased by 60% between 2010‑11 and 2012‑13.

Image Description

The graph shows reports and assistance requests received by NCECC by fiscal year. In 2010-2011, 5,469; in 2011-2012, 6,428; and in 2012-2013, 8,726.

Case complexity and the increased volume of reports have an impact on NCECC's ability to assign and process reports in a timely manner. For example, technological advancements allow users to evade detection, encryption causes delays, and ISPs data retention times impact the securing of evidence. Immediately upon review of each report, a risk assessment is completed to assign priority files. Based on RCMP data, from April 2010 to July 2013, roughly one third (36%) of NCECC files were assigned and concluded within 100 days; approximately 50% of files were processed between 100 and 300 days. Over the same period, NCECC had a backlog of 1,725 unconcluded files, most of these having been at the NCECC between 31 and 200 days.

The reports deemed to be further actionable by the NCECC are converted into investigative packages, one of the key outputs of NCECC Operations, and subsequently forwarded to law enforcement agencies in Canada or internationally. The volume of these investigational packages has decreased over the last three years by 30% (from 755 to 533). Essentially this illustrates that, while requests for services have actually been increasing, the number of investigative packages (outputs) produced showed a declining trend. NCECC notes that this reflects improved operational processing through the consolidation of multiple files regarding a particular subject into a single package, or files targeting multiple suspects. This reflects significant effort by NCECC to streamline the development of packages and to bulk files to enhance efficiency. It should also be noted that all investigative packages are not “considered equal” (i.e. preparation of packages for smaller, less complex cases requires a lower level of effort while packages for larger cases require an increased amount of work). For example, in a major project (nationally or internationally) the NCECC produces one investigative main package. This package will then remain open allowing for other related reports to be added to the main file.

Perspectives among respondents regarding the usefulness of NCECC investigative packages differ significantly between Canadian and international agencies. Most law enforcement agencies from Canada raised concerns with regards to the timeliness of NCECC packages, with delays being attributed to resource or staffing issues, volume, persistent backlog or operational issues. Delays in receiving investigative packages from NCECC are seen to have an adverse impact on law enforcement agencies' ability to conduct investigations in a timely manner. Respondents otherwise expressed generally positive views with the information contained in NCECC investigative packages. Some issues were identified regarding accuracy of information; however, these did not seem to be a general representation of all NCECC files. On the other hand, views among international law enforcement agencies tend to be favourable. These interviewees are satisfied with the packages they receive from NCECC, finding them to be timely, accurate and complete. The divergence of perspectives among domestic versus international law enforcement agencies may be due to the different roles played by these agencies and by their expectations of NCECC.

Another key coordination role from NCECC is requesting information from Internet service providers where that information is not available and required for investigations. To this end, a Law Enforcement RequestFootnote 36 is sent to Internet service providers to obtain a suspect's customer name and address. The information is then passed along to the appropriate law enforcement jurisdiction for investigation. This information is critical and must be requested and obtained quickly, especially since the retention period varies across companies and ranges from as little as seven days up to two years. Between 2010-11 and 2012-13, the volume of requests sent to Internet service providers decreased by 55% (from 690 to 311), while the average response time from Internet service providers improved, going from 11.1 days to 4.43 days.

Support to Law Enforcement Agencies

According to interviewees, the National Strategy is considered to be delivering key benefits with respect to enhancing investigative coordination and support to law enforcement agencies. In terms of overall coordination, the Strategy is cited as a benefit for coordinating investigations nationally and internationally. Respondents state that the Strategy fills an important gap and that both Cybertip.ca and NCECC “are major players in fighting child pornography crime”.

NCECC is seen to be an appropriate body for coordinating major national investigations. For example, NCECC led three major national projects since 2009-10. Respondents cited specific examples of NCECC case coordination including three major projects: Snapshot IFootnote 37 , Snapshot IIFootnote 38 and Project SalvoFootnote 39. Case summaries show that a great number of law enforcement agencies (between 9 and 35) were involved in these cases, which are indicative of coordination work required from NCECC.

Interviewees noted that NCECC plays a critical role in facilitating the international component of investigations and that international coordination is complex and resource intensive. As an example, following his deportation from Cambodia, Canadian Daniel Lavigne was arrested for alleged child sexual offences committed in Canada. Many partners were involved in the investigation led by NCECC, including Passport Canada, the Ontario Provincial Police, the Canada Border Services Agency, the Cambodian National Police, the Hong Kong Police Department, RCMP Liaison Officers in Bangkok and Hong Kong, and a non‑governmental organization in Cambodia.

Respondents stated that NCECC understands international protocols and agreements pertinent to investigations. However, interviewees raised questions about NCECC's current capacity to coordinate cases in a timely and effective manner. These concerns have caused two of the Canadian law enforcement agencies interviewed to contact other national and international agencies directly rather than going through NCECC. This may hinder efforts towards a centralized and nationally coordinated approach.

Interviewees also closely associate NCECC's investigative support with training, and they express mainly favourable views regarding training initiatives. NCECC provided 32 training sessions (seven different courses) between 2008-09 and 2012-13 and trained 592 participants. Sessions provided training on various investigative tools (e.g. the Child Exploitation Tracking System, victim identification digital imaging) and other Internet child sexual exploitation subject matter. No data were available on the impact of these courses. By way of example, NCECC provided training on peer-to-peer investigations to more than 45 investigators in Quebec in January 2013. Projet Mainmise, a child sexual investigation announced in November 2013 by the Sûreté du Québec in which 28 individuals were arrested, mainly involved peer-to-peer investigative work across multiple jurisdictions.

Some law enforcement representatives expressed concerns that access to training and annual subject matter expert conferences is being curtailed due to budget and travel constraints even though they say more training is needed to keep pace with new demands. More specialized training is also seen to be needed (victim identification, behavioural profiling, digital technology and covert operations).

Investigative support from NCECC to law enforcement agencies takes many other forms. For example, NCECC provided several law enforcement agencies (including le Service de police de la Ville de Montréal, RCMP Victoria and Toronto Police Service) with assistance on the categorization of significant quantities of seized child pornography material, forensics and the execution of search warrants, including on the major projects previously identified. Victim identification work was cited numerous times as beneficial to law enforcement agencies. NCECC also produced fact sheets on social media systems/fora (Omegle and 4Chan) being used by offenders to share images. These are designed to assist Canadian child sexual exploitation investigators and are developed based on operational and investigator needs and requirements. No information on the usefulness of these products was collected. Nonetheless, NCECC states that it has received requests from law enforcement agencies for other fact sheets, suggesting a certain degree of interest.

On the international front, NCECC is seen by interviewees to be providing excellent support and assistance to international investigations. One international respondent described NCECC as a “leading light” noting its contributions to victim identification and international training. For example, the RCMP developed a Victim Identification LaboratoryFootnote 40 to help locate and identify child victims who are depicted in sexual images. This portable tool is set up at conferences where police officers are able to securely view redacted child abuse crime scene photos from unsolved international cases in the hopes of providing new leads to investigators. Based on NCECC data, this tool provided hundreds of investigative leads and helped advance several national and international investigations so far.

Cybertip.ca also supported law enforcement agencies with assistance and information for investigations, for example, by providing information about specific service providers, Websites or URLs to law enforcement agencies.

Information Technology Systems and Tools

Specialized information technology systems and tools play an important role in supporting the work and coordination required for analysis and investigation of child sexual exploitation cases. One of the main systems sponsored by the National Strategy is the Child Exploitation Tracking System (CETS). Originally developed by Microsoft, in cooperation with the Toronto Police Service and other Canadian law enforcement agencies, CETS aimed to help investigators to identify suspects, and gather and share evidence and information across jurisdictions to support investigations, while avoiding duplicative work. NCECC was responsible for the roll-out of CETS as the national system for Canadian law enforcement agencies.

Most law enforcement agencies were critical of the tracking system, suggesting it had not lived up to expectations or achieved full functionality, and required law enforcement agencies to enter information that was already entered in other police systems. This finding is consistent with the two previous evaluations in 2006-07 and 2008-09, which also identified issues with the implementation of the Child Exploitation Tracking System. NCECC recognizes that there have been problems with the system and supports the idea of a single system that could be used by all law enforcement agencies. NCECC has been examining a new technological solution as well as potential new system providers to replace this system. However, a business case and implementation plan have not yet been developed to address the technological limitations of the tracking system. NCECC stated a business case had not been required up to this point.

In the absence of a fully-functional Child Exploitation Tracking System, law enforcement agencies mentioned using a variety of other systems, mostly other police information tracking and case management systems. Lack of a fully operational centralized system might impede some law enforcement agencies from having access to the latest information regarding cases and there is a risk of duplication or missed opportunities. Canadian law enforcement agencies felt that a centralized system to coordinate work could help minimize the risk of duplication between NCECC and other law enforcement agencies.